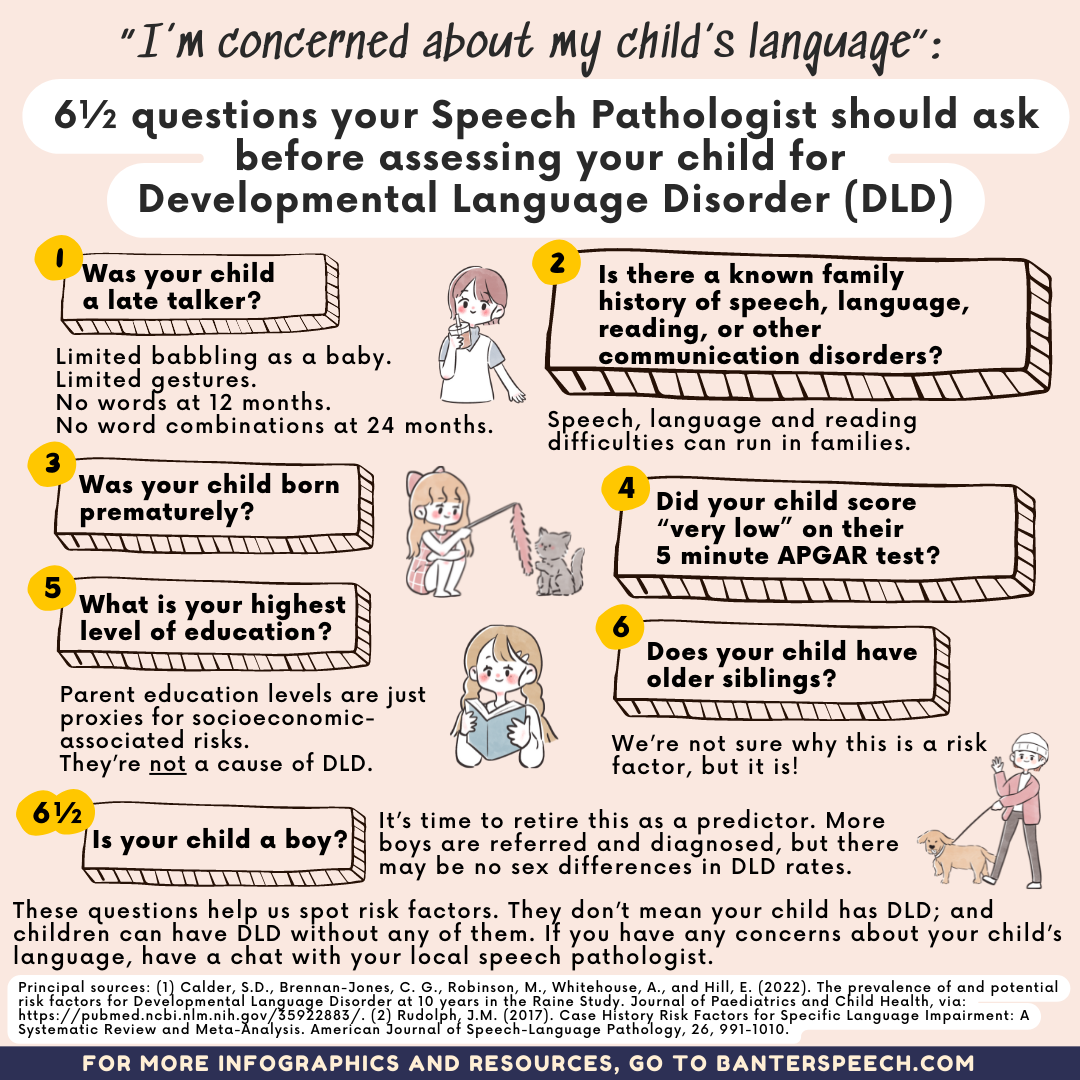

“I’m concerned about my child’s language”: 6 1/2 questions speech pathologists should ask before assessing your child (2022 update)

I ask families lots of questions before I assess a child with suspected communication challenges. My pre-assessment questionnaire is long and I know it takes a while to complete.

But every question has a purpose.

When a family comes to me with concerns about their child’s language skills or development, some questions are more important than others:

1. Was your child a late talker?

Early signs and symptoms of potential Developmental Language Disorder (DLD), include:

- limited babbling as a baby;

- limited gestures; and

- late talking (Hagan et al., 2008).

In particular, a lack of word combinations at 24 months is a significant predictor of language disorders (Rudolph & Leonard, 2016).

However, many late talkers catch up:

- a lack of word combinations at 24 months only identifies about half of children with DLD (Rudolph & Leonard, 2016);

- many late talkers spontaneously recover by early school years, and do not have DLD (e.g. Ellis Weismer, 2002); and

- early language performance alone is not enough to identify children who will go on to have chronic difficulties with language (Dollaghan, 2013; Leonard, 2013).

To make things more complicated, some children hit (or exceed) early language milestones, but then go on to have DLD (e.g. Poll & Miller, 2013).

2. Is there a known family history of speech, language, reading, or other communication disorders

Many speech pathology researchers think there is a strong genetic element in developmental communication disorders, including DLD. Speech, language and reading difficulties tend to run in families.

For example, Rudolph and Leonard (2016) found that a lack of word combinations at 24 months combined with a family history of communication disorders resulted in the identification of almost 90% of children with developmental language disorders.

3. Was your child born prematurely?

Prematurity is a known risk factor for delayed language development, including late talking (e.g., Sanchez et al., 2017). (This may also be one reason why so many premature twins are referred for language assessments.)

4. Did your child score “very low” on their 5 minute APGAR test?

APGAR is named after Dr Apgar in the 1950s, but also referred to by the backronym* “Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, and Respiration”.

Children who scored ‘very low’ on their 5-minute APGAR test are at heightened risk of going on to develop a language disorder (e.g Rudolph et al., 2017).

5. What is your highest level of education?

It’s important for speech pathologists to be transparent about why we ask this question:

- According to Johanna Rudolph of the University of Texas at Dallas and colleagues, children of mothers who did not finish high school are at a heightened risk of language delays and disorders.

- Maternal and paternal education levels are often used as proxies (stand-ins) for the socioeconomic status of the child. For example, as we explain in more detail here, two measures used by the OECD to represent socioeconomic background are:

-

- the highest level of the father’s and mother’s occupation; and/or

- the index of economic, social and cultural status, based on three indices: the highest occupational status of parents; the highest educational level of parents in years of education; and home possessions.

- We know that low household income is a risk factor for language delays (e.g. Armstrong et al., 2017). But, in practice, it’s difficult for speech pathologists to ask families questions about their socio-economic status – especially before their child’s first assessment. It can feel intrusive and rude – not a great way to start a therapeutic relationship with family you have yet to meet!

I want to be clear: a child’s language difficulties are not caused by the mother or father’s low education. Instead, low education levels are simply an indicator that may point to socioeconomic and other factors that increase a child’s risk of language difficulties.

6. Does your child have older siblings?

Systematic reviews have found that having one or more older siblings is a risk factor for potential language difficulties (e.g. Rudolph et al., 2017). We’re not sure why.

It may be related to the quantity and/or quality of parent/carer interactions with a younger child when the parents/carers are also managing older siblings. It may also have something to do with the interactions between the child and his/her older siblings, which in some cases may reduce the need for the child to communicate wants and needs independently. I’m not aware of any good quality recent research on this point, so these observations are speculative at best.

6½. Is your child a boy? (It may be time to retire this one as a risk factor!)

We used to think that being born male increased a child’s risk of DLD (e.g. Rudolph et al., 2017). More recent evidence suggests that – although more boys are referred to speech pathology services – there may be no statistically significant differences between rates of DLD in boys and girls (e.g. Calder et al., 2022).

If this is true, it means there is a referral bias for boys that leads us to assess and diagnose more boys than girls with DLD, and to miss lots of girls with DLD. We need to get better at spotting girls with potential language difficulties and making sure that they get assessed and treated. For example, we know that females with DLD are more than three times more likely to be victims of sexual abuse than females without DLD (Brownlie et al., 2007).

Other risk factors I’d like to know but can’t ask about in a pre-assessment questionnaire

We know about other risk factors for DLD, including a child’s exposure to alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs in utero (i.e. while the mother was pregnant with the child). For example, children of mothers who smoked while pregnant at 18 weeks are more than 2.5 times more likely to have DLD than other children (e.g. Calder et al., 2022).

I don’t ask these questions in my pre-assessment questionnaire because I don’t want parents to feel guilt or judgment when their child might need help. But I do want parents and potential parents to know about the dangers of smoking and drinking while pregnant, including an increased risk of a child having DLD (or another language disorder), or being born with fetal alcohol syndrome.

Bottom line

- If your child falls into one or more of the risk categories identified above, please don’t panic! Having one or more of these risk factors doesn’t on its own mean that your child has a language disorder. But if you are concerned about your child’s language, please have a chat with a local speech pathologist.

- Conversely, if you are concerned about your child’s language development for any reason, contact a speech pathologist for a confidential chat – even if your child demonstrates none of the risk factors or predictors flagged in this article. Some children later diagnosed with DLD come to assessment with no known risk factors.

- Any discussion of risk factors and predictors is confronting. I wrote this article to explain why I ask families so many questions before I meet them. I also want to increase public knowledge of DLD risk factors and DLD itself.

Principal sources:

Calder, S.D., Brennan-Jones, C. G., Robinson, M., Whitehouse, A., and Hill, E. (2022). The prevalence of and potential risk factors for Developmental Language Disorder at 10 years in the Raine Study. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, via: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35922883/

Rudolph, J.M. (2017). Case History Risk Factors for Specific Language Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 26, 991-1010.

Related articles:

- Developmental Language Disorder: A Free Guide for Families

- Why I tell parents to point at things to help late talkers to speak

- “My toddler doesn’t speak at all!” Don’t panic – get informed

- Language therapy works. But can we make it better?

*As a morphology nerd, I love the term “backronym”, a noun meaning “an acronym deliberately formed from a phrase whose initial letters spell out a particular word or words, either to create a memorable name or as a fanciful explanation of a word’s origin.”

This article also appears in a recent issue of Banter Booster, our weekly round up of the best speech pathology ideas and practice tips for busy speech pathologists, speech pathology students and interested readers.

Sign up to receive Banter Booster in your inbox each week:

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.