Language therapy works. But can we make it better?

Every year, we work to improve our practice. This year, we revisited what we know about the effectiveness of our language therapy for children with Developmental Language Disorder (DLD). We looked at the research – including an important systematic review published in March 2021 – talked to our clients, and reviewed our clinical data to see if we could distil the key ingredients of effective language therapy to improve the quality of our services for clients.

Having done this work, we thought we’d share our key findings:

A. Good therapy foundations

Joint attention

Communication is based on joint attention. Children learn more when their attention is directed at the thing you are trying to teach them (e.g Eriskon, 2008). Therapy that gets and holds a child’s attention is more effective than therapy that doesn’t (e.g. Gillam & Loeb, 2010).

Therapy Intensity

Many people think that intense therapy is better than less intense therapy (e.g. Gillam & Loeb). But more isn’t always better (e.g. Kamhi 2014): increasing the frequency of language therapy does not always improve outcomes (e.g. Ukrainetz et al., 2009; Fey et al., 2013).

Children do better with:

- low doses of therapy, frequently; or

- high doses of therapy, infrequently (Schmitt et al., 2017).

Learning plateaus and threshold effects exist for both language and literacy (e.g. Ambridge et al., 2006; Riches et al., 2005). There may be points of ‘diminishing returns’, where little additional benefit is derived from more language therapy (e.g. McGinty et al., 2011). You can read more about language therapy ‘dosage’ here.

Human interaction

The evolution of human communication is founded on interactions between people cooperating for a common purpose (Tomasello, 2017). This means most people are ‘biologically primed’ to learn to be self-aware and aware of others, to process facial expressions, to have joint attention, and to take-turns in interactions with others.

Some children need help to develop these skills. That’s one reason interactive learning is better than learning passively; and why naturally interactive activities like shared reading is such a useful language learning technique with young preschoolers.

Feedback

To improve communication skills, children need feedback on their attempts. Feedback can be verbal or non-verbal or both. Feedback should be specific to the goal (not general platitudes, like ‘good talking’). Too much feedback (positive or negative) can be counterproductive:

- kids tune it out; and

- it disrupts the natural flow of conversation.

Too much negative feedback can be demoralising. In early language therapy, recasting is more productive than correction.

Rewards

We’re ambivalent about the use of external rewards in therapy. But there is no denying that the day-to-day practice of language therapy is heavily indebted to behaviourist learning principles.

Most therapists recognise the importance of internal motivation and the benefits of rewards in learning. In practice, external rewards like stickers and tokens can help some children do better in therapy, e.g. by increasing their attention and motivation to do the work, to help them increase their awareness of feedback on their performance and to reinforce new learning.

B. Some therapy design tips, based on principles of learning

Target multiple goals in each therapy session

We should target different kinds of language problems within each session. For example, in my 45-minute language sessions with preschoolers and school-aged children, I aim to target at least 4 different language goals, including to treat language content, form and use difficulties.

We’ve known for a while that mixing activities can improve motor learning in some conditions (e.g. Wulf & Shea, 2002). There’s growing evidence that ‘interleaved’ practice or ‘interleaving’ also works on cognitive tasks. Mixed practice may promote general language development because it allows children to compare different kinds of problems more readily, and to make more connection. It’s also possible that mixed practice creates distributed learning conditions, which help students retain information and learn more effectively. You can read more about some of this research here.

Cycle goals across sessions to space out practice of each goal

Short bursts of treatment on a goal spread over weeks may help children to learn new skills better than intensive treatments squeezed into one session or taught over consecutive days (e.g. Riches et al., 2005; Smith-Locke et al., 2013). This is called the ‘spacing effect’ and has been studied extensively in the context of improving study skills.

Another way of saying much the same thing is to say that distributed practice – having intervals between targeting the goal – is more effective than massed learning (e.g. Baddely, 1997). Over 100 years of research and over 300 studies show the benefits of distributed learning across a variety of different cognitive domains (Bruce & Bahrick, 1992).

Taken together, the research suggests that spaced practice exploits a fundamental human learning mechanism that boosts both initial performance and retention (Bahrick & Phelps, 1987; Kamhi, 2014). There is good evidence that spacing and distribution of teaching episodes is particularly useful for children with language learning difficulties and may be even more important than treatment intensity and dose (e.g. Riches et al., 2005; Yoder et al., 2012).

Build retrieval practice into your sessions

These require the child to recall something they have learned previously and to re-produce the information.

Sometimes, in therapy, children can spend too long simply re-reading, imitating or listening to language from set materials. But retrieving information from memory facilitates long-term retention (e.g. Bjork, 2011). This may be one reason why spelling and writing benefit reading (e.g. Graham & Herbert, 2010). It may also explain why doing practice tests (for academic tasks), making your own learning materials (rather than just using someone else’s materials), and handwriting your own notes, are useful ways to learn and remember things. You can read more about retrieval practice here.

Build elaboration and self-explanation practice into sessions

Most children are naturally inquisitive – asking their parents and others lots of ‘why’ questions. Some children are good at explaining ideas to themselves.

Some children need help to learn to ask ‘why’ questions when listening to language or reading. Others need to learn to explain things to themselves to check for comprehension. These skills – ‘elaborative interrogation’ and self-explanation – can be taught and learned. You can read more about them here.

While targeting language, introduce related facts about the child’s environment and the bigger world

From an evolutionary perspective, humans are primed to pay attention to the biological and physical world around us. But some clients with developmental language and other developmental disorders need help to develop basic primary knowledge about their physical environment, including basic category and sequencing skills.

It’s also important for children to learn about their specific cultures, world and universe. Having a vast store of quickly available, previously acquired knowledge enables the mind to take in new information in less time and with less effort and to link it to existing knowledge (Hirsch, 2003). Helping children to know more about the world they live in: speeds up basic comprehension and leaves working memory free to make connections between new and previously learned information; helps children to make sense of word combinations that have ambiguous meanings, helps with inferencing and helps older students to understand metaphor, idiom, irony, and other higher level language uses.

You can read more about the importance of background information here.

Leave room for play (for children and adults of all ages) – especially for social use of language goals

Play is often discounted, even denigrated. ‘I’m not paying you to play games with my child.’

But play serves an important biological purpose: Through no-stakes, imaginary world practice, kids learn vital life skills through self-directed play, including many language and social skills essential for life success. Peer development and cooperation skills are often acquired through play; and social skills can often be improved more meaningfully through planned peer-peer practice in play, rather than adult-child interactions, which often look very different (e.g. Cordier et al., 2013).

C. Some tips for choosing goals

Target language goals (not sub-skills or processes)

Language is complex. For children with language and learning disorders, improvements can be slow and therapy can be hard-going. It’s understandable that families (and some speech pathologists) are drawn to well-marketed programs that promise quick fixes. Intuitively, we can understand why some people think that working on sub-skills – like auditory processing or working memory – might result in improvements to language skills.

But, unfortunately, the research to date tells us that it doesn’t.

Instead of working on sub-skills and processes in isolation, we should spend our limited therapy time on functional activities that help children to comprehend and use language – even though it is often hard work.

Target goals that we know can be improved by language therapy

Identifying effective interventions is a fundamental aim of clinical practice for children with DLD. If targeted properly, language intervention may not only improve short term language outcomes but also medium and long term influences on global development (Rinaldi et al., 2021).

Evidence to date tells us that some language therapy targets can be pursued more effectively than others. For example, there is high level evidence for the effectiveness of language therapy to improve:

- phonological expressive skills (e.g. some contrast therapies, therapy including auditory discrimination and phonological awareness training);

- expressive morphosyntactic skills (e.g. with recasts or reformulations of the child’s production by an adult in conversation, as well as explicit suggestions, cues and prompts related to the grammatical rule); and

- narrative skills (particularly interventions that help students to understand causal and temporal relationships).

There is some evidence to support the effectiveness of language therapy interventions to improve expressive vocabulary (e.g. Law et al., 2003).

By contrast, there is little evidence to date that that receptive language (e.g. receptive phonology, vocabulary) interventions work (e.g. Law et al., 2003; and Rinaldi et al., 2021). Receptive language targets are difficult to isolate in therapy (we never truly know what is going on inside a client’s head). Some researchers think there is no point trying to separate expressive and receptive language skills because all aspects of oral language interact and feed into each other as parts of a complex system. There are fewer clients with receptive language difficulties (making it harder to recruit them for studies). In some cases, severe weaknesses in language comprehension are associated with weaker cognitive skills (even if they remain within normal limits overall), making treatment more challenging (e.g. Rinaldi et al., 2021). Some clinicians (including me) think the best way to improve receptive language skills (and to monitor comprehension) is to work on expressive language goals.

Encourage language skills to be carried out in meaningful contexts

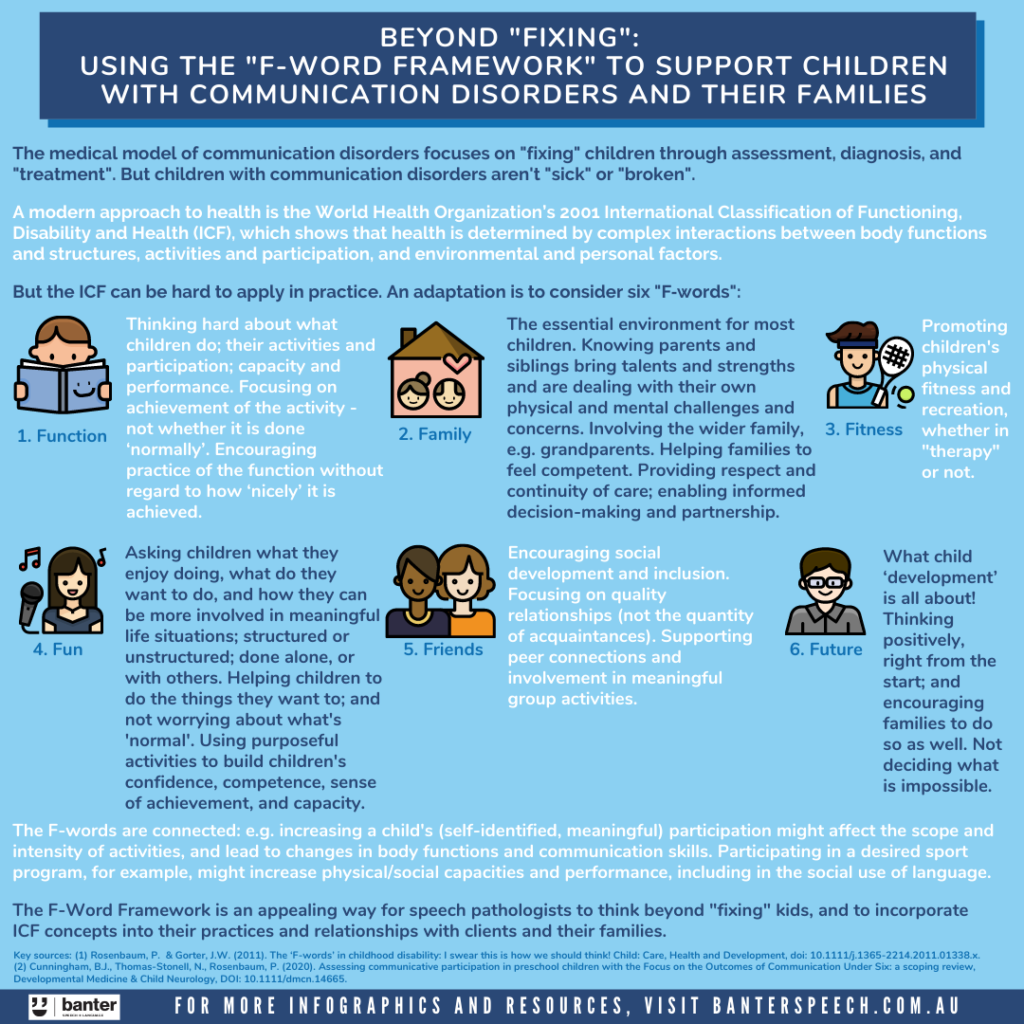

In our practice, we apply the F-Word Framework (Rosenbaum and Garter, 2011). This requires us to focused goals that are relevant to clients and their families, and that support the client to communicate and participate in real world situations that matter to them:

Interventions aimed at encouraging clients to use language in real world situations that matter to them (e.g. at home, at school, in sport, when playing with friends) is thought to help a client’s language gains to be generalised to the real world (e.g. Rinaldi et al., 2021).

Target goals that are important to the child and the family now

Developmental norms and language assessment results are important. But it’s more important to understand the family’s key concerns – the things they want you to work on right now – especially if it is affecting relationships.

For example, if a parent gets really stressed and annoyed when their child leaves out her articles or makes errors with a particular irregular plural like ‘mice’, this is a legitimate goal, even if, developmentally, it isn’t next in sequence or (from the speech pathologist’s perspective) particularly unusual at the age.

Similarly, if the child gets really frustrated about his inability to explain cause and effect relationships in words, and lashes out at people who don’t understand him, then working on ‘because’ and ‘so’ at the sentence level is a better goal than a few pronoun errors that don’t affect his ability to be understood.

I’ve worked with a teenager whose only goal was to write effective social media posts. I’ve worked with adults who are sick of mis-ordering their lunches. I’ve worked with people with lifelong language issues who simply wanted to tell their story to others in an effective way. All three were important and meaningful goals. But you won’t find any of them on a developmental management chart.

Target goals that are likely to be important to the child in the future

Let’s look at some examples:

- If you are seeing a preschooler who is starting school in a month, working to help the child understand how to follow multi-step instructions, to ask simple questions, and to build phonological awareness are solid goals. Sharing evidence-based information on school readiness with families is also important.

- If you are working with a preschooler who snatches at things or demands them directly, indirect question structures are functional because adult strangers, teachers and even parents are hard-wired to interpret direct requests from 4-year-olds and older kids as rude or insolent.

- If you are working with a worried student in Year 6 who has difficulty making friends or dealing with change, then supporting his transition to high school (e.g. by teaching how to join in an activity, ask for help if you are lost, read a timetable, or use a diary to remember things that are due) should be a priority.

Target complex goals, rather than simple ones

Over the last 60 years, we’ve amassed lots of information about typical language development (e.g. Nippold. 2014). But not all goals are of equal importance when working with children with developmental language disorders. Knowing what to treat and when is essential.

For example, when working on syntax, too many of us work on early developing targets, like ‘-ing’, <in> and <on>, even though there is little evidence that children with language disorders have long term problems with these targets. Many speech pathologists are still trained in outmoded mental models like Brown’s so-called 14 morphemes, and operate under the mistaken assumption that these need to be mastered before you can move on to more advanced topics. It’s total nonsense.

With limited time, we need to be more ambitious and judicious in selecting goals. For example, we should target:

- complex syntax, like coordinating conjunctions, subordinating conjunctions and relative clauses, because typically developing 4 and 5 year-olds use it to express their thoughts and feelings using complex language and our clients need these skills too (e.g. Barako Arndt, K. & Schuele, C.M., 2013);

- verb tense and agreement problems early (e.g. third person singular verbs, regular past tense verbs, auxiliary verbs like ‘does‘ and ‘has‘, and problems with the copula (different forms of ‘is’), because they are often very difficult for children with language disorders to master (e.g. Bedore & Leonard, 1998);

- verbs of thought like ‘know’, ‘think’, ‘wish’ because they lead to object clauses and increase the diversity of verbs used (e.g. Hsu, 2015);

- narratives because humans are primed to tell stories; there’s a strong link between the ability to understand and tell stories and later literacy and academic success (Paris & Paris, 2003); young children with language delays have great difficulty making up stories; narrative skills can help reading comprehension; and once kids have learned how they work, stories provide an easy way for them to comprehend and recall facts (Hudson & Nelson, 1983). Producing narratives provides a bridge between spoken and written language (Dunst et al., 2012). Story making can also be used to teach all aspects of language and literacy, including syntax, morphology, narrative structure, reading, writing and spelling.

For school-aged children, teach oral language and written language (reading and writing) together

Oral language skills (talking and understanding) and reading skills are linked; oral language and reading skills are mutually beneficial. Improvements in spoken language skills improve reading skills, and vice versa. Oral language and reading skills piggy back on each other during the school years (Snow, 2016). If one is impaired or delayed, the other suffers. For example:

- children with speech-language disorders (diagnosed or not) are at a high risk of having reading problems, although developmental language disorders and dyslexia are not the same thing;

- the Simple View of Reading tells us that reading comprehension is dependent (amongst other things) on language comprehension skills;

- children with reading problems may have problems learning new academic words;

- many children with language or reading problems (or both) have difficulties with higher level language skills, like idioms, similes and metaphors, analogies, homophones, homonyms, and homographs and sayings and proverbs; and

- children with language or learning disorders are more likely than others to struggle with writing (Katz et al., 2008); have writing problems that outlast reading and other learning problems (Alley & Deshler, 1979); and have problems with writing that persist well into adulthood (Mortensen et al., 2009). You can read more about this here.

For school-aged children, work on goals that are related to the curriculum

This seems obvious, but is sometimes forgotten. Children get enough homework without having language therapy home exercises piled on top. For older children, in particular, language goals should often be pursued while working on school homework and assignments. For example:

- for early primary school children, we might target subordinating conjunctions and narratives using a topic being covered in class (e.g. animal habitats); and

- for older high school students, we would target an academic verb like ‘discuss’ in the context of practice exam questions using the word, for example, recent Business Studies, English, History or Biology Higher School Certificate Exams.

Target goals in different and meaningful contexts

To enhance learning, we need to vary both the complexity and the conditions of practice (Bjork, 2011). This may be as simple as practicing the skill in different places with different people (one of the key advantages of home practice).

Working on language in a variety of contexts is important (e.g. Gillam et al., 2012). This is especially true for higher level language targets, e.g. idioms and metaphors. In many of our oral language therapy resources for school aged children, for example, we include a variety of exercises including listening to stories, interpreting idioms, answering questions, comparing and contrasting objects and characters, discussing and defining academic vocabulary, justifying opinions, drawing inferences from information given, divergent thinking, cultural knowledge about the world, language from myths and legends, morphological awareness and story generation with semantic constraints. We also work on complex sentences used in verbal reasoning tasks. You can see examples of this type of approach in our Listen, then Speak resources, Level Up Language course and Exam Verbs library.

If a child needs help in one particular context, e.g. ordering food at a school canteen, the best place to work on that goal may be the canteen. In situations like these, scripts and video modelling to pre-practice the task can be helpful.

Collaboration with educators and others to share information, goals, and supports

Language therapy is a team sport. Ideally, it involves the child, the speech pathologist, the child’s parents or carers, educators, general practitioners and other medical and allied health professionals all pulling in the same direction – and in the best interests of the child.

Things can get complicated when school starts. The speech pathologist should coordinate with learning teams to work out how best to support the child and the school. Speech pathologists can help with evidence-based suggestions to help children with language cope with the curriculum and teacher training on things like risk factors for developmental language disorders and symptoms to look out for.

Speech pathologists need to listen carefully to teachers, to understand the effects of the child’s language issues on how the child is participating at school. They also need to share information about the sometimes long term social effects of developmental language disorders; and the heightened risks of behavioural and emotional issues.

Teachers can help by spotting children with language difficulties early and be referring them for assessment. Depending on assessment results, teachers, learning support teams, speech pathologists and parents can work out how best to support the child. Sometimes, this means ‘dividing’ up supports, for example, the speech pathologist focuses on oral language comprehension, and the school focuses on reading and writing supports. Often, in practice, it’s more complicated than that for the simple reason that language and literacy are so interconnected. Things can get even more complicated when the child has some behavioural, attention or mental health issues, and/or if the child has additional diagnoses, like ADHD, that also often affect language development.

D. Therapy techniques – common elements

There are lots of different language therapy techniques, and a full review is beyond the scope of this (already very long) article. Some are speech-pathologist-directed; while others are more child-centred. Our therapy tends to mix both approaches, depending on the child and their needs.

For younger children, many speech pathologists use implicit approaches, like imitation, modelling and recasting. For older children, therapy tends to take a more explicit or direct approach. I think we owe it to all clients – even preschoolers – to explain what we are working on and how.

For example, recent evidence suggests that interventions are more effective if they include the use of explicit instructions to teach grammatical forms to children with DLD (e.g. Rinaldi et al., 2021)

Many techniques share a few common elements:

- Clear language models/input: We should always provide well-formed language models to clients (e.g. Kamhi, 2014; Bredin-Oja & Fey, 2014). The presence of function words (often produced as weak syllables in connected speech) can help children to hear words, phrases and clauses (e.g. Bedore & Leonard, 1995). For example, in the sentence ‘The girl went to the beach’, the weak syllables ‘to’ and ‘the’ help children to take special note of the strong syllables ‘girl’, ‘went’, and ‘beach’.

- Repetition: Late talkers and children with language disorders benefit from lots of repetition (Alt, et al., 2020; Plante et al., 2018). Techniques like modelling and focused stimulation often employ many examples of the target. You can read more about modelling and focused stimulation here.

- Increase signal, decrease noise: Many therapy techniques are based on the idea of making the target clearer, and reducing emphasis on the things that are not the target. Word order, for example, in sentence completion tasks, can be manipulated to ensure that the stress is on the target, e.g. if working on his/hers, the speech pathologist could say: ‘The cat is not hers. It’s his. The cat is his.’

- Responsiveness to the child: As noted above, feedback on the child’s attempts can make a big different. Feedback can be evaluative, with right/wrong signals sent by the therapist; or can take the form of recasting, expansions, and extensions. You can read more about recasting and expansions here.

For older children, direct instruction in context can be more efficient.

- Ukrainetz, 2015, for example, recommends that therapy for older school-aged children should provide repeated opportunities for skill learning, intensity of instruction, systematic support (including scaffolding) of targeted skills, and an explicit focus on the language skill in question, or ‘RISE‘.

- Lessaux et al., 2014, suggests the Academic Language Instruction for All Students (ALIAS) approach to vocabulary instruction, including teaching words in context with books (not lists), choosing Tier 2 academic words, explicitly teaching word knowledge through etymology, phonology, orthography, morphology and related words, combined oral/written language tasks, lots of repetitions, with distributed practice and a focus on small group interaction.

- Ebbels, 2014, in the context of her metalinguistic ‘shape coding’ grammar intervention uses a combination of shapes, colours and arrows to indicate parts of speech and morphemes in sentences.

Interestingly, many of these ideas and approaches share features with Direct Instruction teaching of secondary knowledge, perhaps reflecting the fact that for many older children with language disorders, language targets need to be explicitly taught, rather than picked from exposure or through statistical learning.

Direct Instruction is teacher directed, explicit and carefully sequenced, with a focus on learning. Often, instruction starts with a teacher model, then practice together, and finally by independent practice – the so-called ‘I do, we do, you do’ method of teaching. Spaced distribution, interleaving and retrieval practice can be built into this form of teaching.

E. Clinical bottom line

As Fey noted way back in 1988, language is way too complex for us to ‘teach’ every form and use to children with language disorders. Language serves too many functions, expresses too many meanings, and can be looked at in too many ways. An infinite number of word and syntax options exist, and language is always evolving. We have to focus on how best to support the child in front of us.

In this article, we’ve highlighted several elements that we think can be used to improve language therapy outcomes for children with language disorders. We’re sure there are many factors we didn’t cover, and there are no doubt many factors that have yet to be discovered. But we’re hopeful this work gives us a framework to keep getting better at language therapy. The plan is now to put all this knowledge into practice; and to make sure we’re providing the best service we can to all of our language therapy clients.

Principal references:

- Kamhi, A. (2014). Improving Clinical Practices for Children with Language and Learning Disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing in Schools, 45, 92-103. Gillam, R.B.,

- Loeb, D.F. (2010). Principles for School-Age Language Intervention: Insights from a Randomised Control Trial, ASHA Leader; January, pages 10-13.

- Ebbels, S. (2014). Effectiveness of intervention for grammar in school-aged children with primary language impairments: A review of the evidence, Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 30(1), 7-40.

- Rinaldi, S.; Caselli, M.C.; Cofelice, V.; D’Amico, S.; De Cagno, A.G.; Della Corte, G.; Di Martino, M.V.; Di Costanzo, B.; Levorato, M.C.; Penge, R.; et al. Efficacy of the Treatment of Developmental Language Disorder: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11030407

More reading on explicit and direct instruction and evidence-based learning practices:

- Dave Morkunas on Spaced, Interleaved and Retrieval Practice

- The Learning Scientists on evidence-based learning techniques

- Dr Lorraine Hammond on Direct Instruction

- Tom Sherrington’s (pretty) summary of Rosenshine’s 10 Principles of Direct Instruction

Related articles:

- Does my child have a language disorder? 6 questions speech pathologists should ask before assessment

- Oral language: what is it and why does it matter so much for school, work, and life success?

- Speaking for themselves: why I choose ambitious goals to help young children put words together

- Following instructions: why so many of us struggle with more than one step

- Parents: teach categories to your kids to ignite language development

- Five ways to boost your child’s oral language and reading comprehension skills with sequencing

- ‘My son (daughter) has been diagnosed with a developmental language disorder. How much treatment should he (she) get? How often?’

- Resources to learn grammar: using auditory bombardment to improve kids’ expression and grammar skills

- Too many stories, not enough facts? Free tips and resources to boost your child’s knowledge and reading comprehension skills

- Help your child to fill in the gaps, join the dots, and read between the lines! (Improve inferencing skills for better reading and language comprehension)

- ‘In one ear and out the other’. FAQs: working memory and language disorders

- ‘Why should I let my late-talker play with other kids?’ Because play promotes learning: here’s why and how

- Speech pathology for kids: Is it time to put away the Pop-Up Pirate and just do the therapy?

- Dyslexia vs Developmental Language Disorder: same or different, and what do we need to know about their relationship?

- 24 practical ways to help school-aged children cope with language and reading problems at school and home

- Your right to know: long-term social effects of language disorders

- Tip of the week: Joint Attention

- The toddler screen debate: are we asking the wrong question?

- Reading with – not to – your pre-schoolers: how to do it better (and why)

- How to improve exam results: 9 free evidence-based DIY strategies (interleaved practice, spacing effect, distributed practice, retrieval practice)

- FAQ: Auditory Processing Disorder

- Can I? Would you? If it wouldn’t be too much trouble…Why our kids need to learn to ask for things indirectly

- My child is having emotional and behavioural problems at school. Should I get his language development checked?

- For reading, school and life success, which words should we teach our kids? How should we do it?

- Not about ‘fixing’: using the ‘F-Word Framework’ to support children with communication disorders and their families

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.