Let’s cut to the chase: when should I seek help from a speech pathologist for my child?

Speech pathologists help people with communication problems. But many of us are not very good at explaining what we do in Plain English:

- We use too many long, pointless words.

- We call ourselves different things in different countries.

- We can’t agree on what to call some communication impairments.

And we’re not alone. Psychologists, doctors and psychiatrists use different words and phrases to talk about communication issues. It’s not always clear whether we’re all talking about the same thing.

This is a big problem: it’s confusing to people and families who need help.

There’s an urgent need for speech pathologists to give people better information about common communication impairments. In this article, we answer some questions about speech pathology and common communication problems.

We want to help you understand what we do and how we can help.

1. Are speech pathologists, speech therapists and speech-language pathologists the same thing?

Yes.

2. What do speech pathologists do?

Most speech pathologists help people with communication impairments. Some of us also help people with swallowing and feeding impairments.** An impairment is a disability.

3. What does “communication impairment” mean?

To survive and to take part in society, we need information: facts and knowledge. One way we get and pass on information is by communicating with others. Communication means sending information to, and receiving information from, others.

Some people have problems sending and/or receiving information. We call these problems communication impairments.

4. What are the most common communication impairments?

Developmental language disorders and speech sound disorders. They affect about 5-8% of pre-school children. If untreated, they can lead to lots of problems including with behaviour and social interaction, reading and writing, school and work success, and mental health.

(a) Are language and speech the same thing?

No.

One way we communicate with other people is through language. Language is understanding and using words and sentences to receive and to send information. We can do this by speaking and listening, reading and writing, or by sign-language. Language includes:

- content: our knowledge of words (vocabulary) and meanings (semantics);

- form: our knowledge of speech sounds (phonology), word forms – e.g. saying “cups” to tell people there is more than one cup, or “climbed” to tell people that the climbing happened in the past (morphology); and how to put sentences together properly (syntax); and

- social use: how to use language appropriately in a given situation, e.g. when having a conversation, giving a speech or telling a story.

Speech means using our voices to make words and sentences. Speech involves both language skills and motor skills (using nerves, muscles and body parts to make speech sounds). For example, to say “banana” we need to coordinate our breath, vocal chords, lips, soft palate, jaw, tongue and teeth to articulate the three “beats” – ba-na-na – in a way that others can understand.

You can have good language skills, but impaired speech skills. For example, you might be able to write or sign fluently, but not be able to speak clearly.

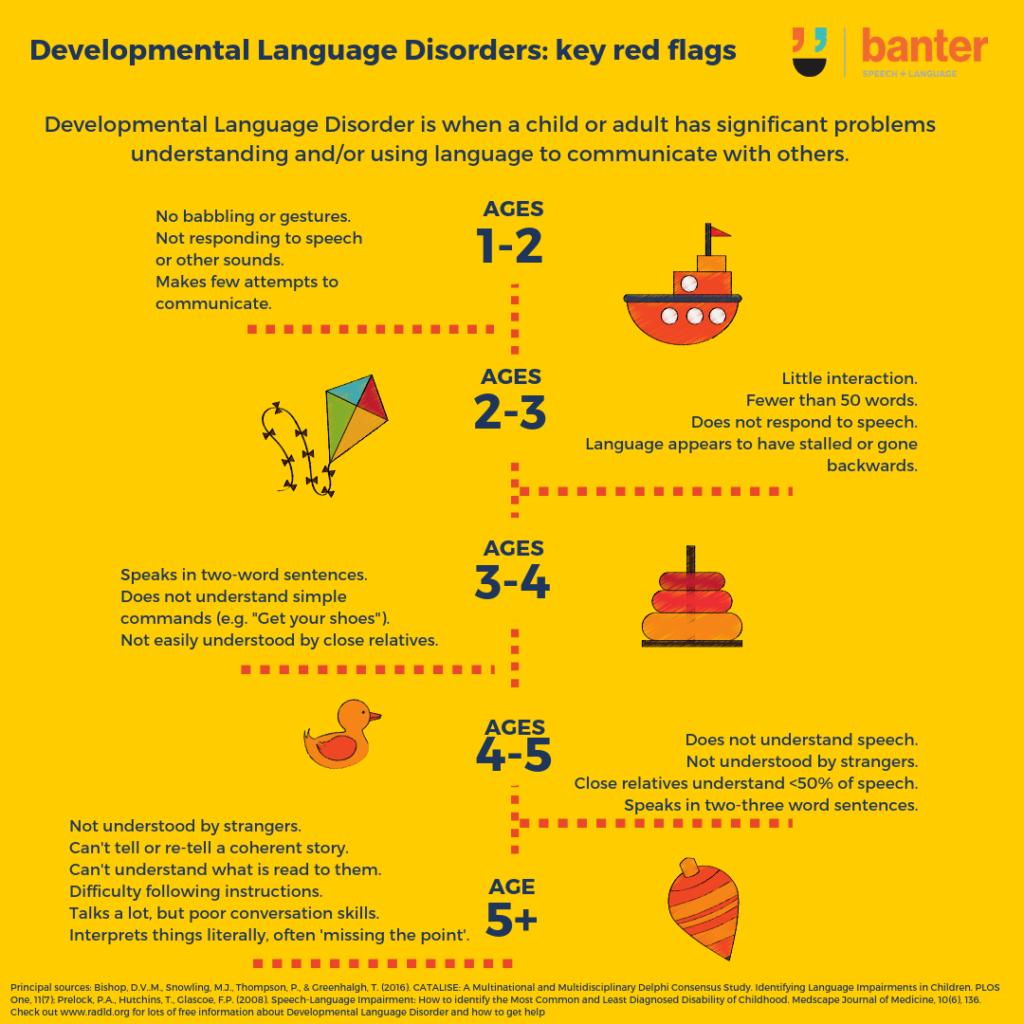

(b) Developmental language disorders

These are problems understanding and/or using language to communicate with others.

Confusingly, speech pathologists and others can’t agree on a single name to call it. Different people in different places use different terms, e.g.

- language delay;

- language disorder;

- specific language impairment;

- language learning impairment; and

- developmental dysphasia (or aphasia).

All these names have their pros and cons. In line with recent academic and professional efforts to reach agreement, we prefer the term “developmental language disorders”.

(c) Speech sound disorders

These are problems saying speech sounds correctly and being understood. If strangers can’t understand your child’s speech, they might have a speech sound disorder.

Speech sound disorders include:

- not being able to say some sounds. You can read more about when children are expected to be able to say different consonants here;

- developmental and unusual error patterns called “phonological processes”. You can read more about 10 common error patterns here; and

- articulation problems, like lisps. You can read more about lisps here and here.

5. When should you see a speech pathologist about your child’s speech-language development?

When any of the following is true:

- You are concerned about your child’s speech, language or communication skills development.

- Your child is having behavioural or psychiatric problems.

- Your child’s communication skills (listening and/or speaking) are well behind the skills of his or her peers.

- Your child is between 1 and 2 years old and:

- isn’t babbling;

- is not responding to speech or other sounds; or

- is making few attempts to communicate with you.

- Your child is between 2 and 3 years of age and:

- does not interact with you or others much;

- has no or very few words (fewer than 50 words);

- does not respond to spoken language; or

- has their language development appear to stall or even go backwards.

- Your child is between 3 and 4 years of age and:

- speaks in two-word sentences at most;

- does not understand simple commands (e.g. “Get your shoes”); or

- is not easily understood by close relatives.

- Your child is between 4 and 5 years of age and:

- speaks in two-three word sentences at most;

- does not understand spoken language;

- is not understood by strangers; or

- is not understood by close relatives at least half of the time.

- Your child is older than 5 years and:

- is not understood by strangers;

- can’t tell or re-tell a coherent story;

- can’t understand what is read to them or listened to;

- has difficulty understanding, following or remembering spoken instructions;

- talks a lot, but is very poor at engaging in conversation; or

- interprets things very literally, often missing the point of what is meant.

6. How do speech pathologists assess communication impairments?

Speech pathologists should get their information from more than one place to make sure they understand the scope of the problem and its effects:

- Client, parent, and teacher reports.

- Observations: in the clinic and, if possible, out in the real world.

- Standardised and other tests to probe areas of strength and challenge.

- Language sampling.

Speech pathologists should look at two things when they assess people with language or speech problems:

- the skills that are impaired; and

- the effect of the person’s communication impairments on their participation in the real world.

These are different things. For some people, a minor impairment (e.g. a lisp) can have a big impact on their quality of life. For others, even a severe communication impairment may not cause many problems.

7. What communication skills do speech pathologists assess?

- Language understanding – also called “receptive language”.

- Language expression – also called “expressive language”.

- Language content, form and use (see above).

- Speech sounds: development of vowels and consonants, developmental error patterns and atypical error patterns.

- Oro-motor skills (nerves, muscles and body parts of speech).

- Fluency.

- Intelligibility: can the person be understood by others?

Often, speech-language assessments are done in stages. We look for the big issues first, then zero in on specific problems.

8. Can children have both developmental language disorders and speech sound disorders?

Yes. We know that:

- around 15% of 3 year olds have a speech sound issues; and

- 50-75% of these children also have a developmental language disorder.

You can read more about this here.

9. What if my child speaks more than one language?

Speaking more than one language:

- does not cause language learning impairments; and

- is an advantage for many children.

At 30 months of age, children who have at least 60% exposure to English will usually have similar language skills to a native English speaker. Children need around 5-7 years exposure to a language to be fluent in it.

A true language impairment will affect all languages a child speaks.

You can read more about language impairments and children who speak more than one language here.

10. Can children with language disorders also have other issues?

Yes. Developmental language disorders and speech disorders frequently happen at the same time as other difficulties, including problems with:

- working memory;

- auditory processing;

- attention, e.g. ADHD;

- hearing problems;

- behaviour, e.g. hitting, kicking, biting other children;

- gross or fine motor impairments;

- reading; and

- general development.

In these cases, it can be a good idea for your child to be assessed by other relevant professionals as well as a speech pathologist, e.g.

- a paediatrician for a developmental assessment;

- an audiologist for hearing and auditory processing assessments;

- an occupational therapist for sensory, gross and fine motor assessments; and

- a psychologist for a cognitive or reading assessment.

Some children with developmental language disorders and speech sound disorders also have developmental disorders or life-long disabilities, e.g. some children with:

- moderate-severe profound hearing loss (although this typically only affects oral language – not signing or speech – if the child is exposed to signing early in life);

- intellectual disabilities;

- Down Syndrome;

- Klinefelter Syndrome; or

- Autism Spectrum Disorder.

11. My child might be stuttering. Where can I find information about evidence-based treatments?

Stuttering is fairly common, and often starts between the ages of 2 and 3 years. There are some great treatments available for pre-schoolers. Stuttering gets harder to treat with age.

You can read more about stuttering and other fluency disorders here. We don’t think there is any link between developmental language disorders and stuttering. However, we know that 30-40% of children who stutter also have a speech sound disorder.

12. My child has voice problems. Should I be concerned?

Voice disorders are probably not picked up as often as they should be and can have a big impact on a child’s quality of life.

You can read more about voice disorders here.

Bottom line

Speech-language communication impairments:

- are the most common of childhood disabilities;

- are often not picked up early enough; and

- can have serious effects on a child’s social, school and later work goals, participation and achievements.

Speech pathologists (myself included) need to do a better job telling the public about common childhood communication impairments. We need to:

- agree on our terms;

- cut out the jargon and speak in Plain English; and

- give families:

- quality information based on the latest research evidence; and

- practical guidance on when, where and how to seek help.

If you have any concerns about your child’s communication skills, please contact your local speech pathologist for a chat.

Principal sources:

- Bishop, D.V..M., Snowling, M.J., Thompson, P., & Greenhalgh, T. (2016). CATALISE: A Multinational and Multidisciplinary Delphi Consensus Study. Identifying Language Impairments in Children. PLOS One, 11(7). Full text can be accessed here.

- Prelock, P.A., Hutchins, T., Glascoe, F.P. (2008). Speech-Language Impairment: How to identify the Most Common and Least Diagnosed Disability of Childhood. Medscape Journal of Medicine, 10(6), 136.

** People use many of the same nerves, muscles and body parts for both speech and swallowing. But they use them in very different ways. At Banter, we focus on speech and language and do not treat feeding or swallowing disorders. For people with swallowing or feeding needs, we are always more than happy to refer them on to speech pathologists with this expertise.

Image: http://tinyurl.com/zbtpfav

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.