My child’s speech is unclear to adults she doesn’t know. Is that normal for her age? (An important research update about child speech intelligibility norms)

Parents ask us this question regularly.

1. New research and evidence-based practice

Thanks to some great new research, speech pathologists have better information to share with families. But clinical speech pathology requires us to do more than just read, summarise, and apply the research uncritically.

To answer parents’ questions about their children’s unclear speech, we have to integrate new information with other peer-reviewed research, our clinical experience, and – most importantly – the real world views, concerns, and goals of the families and children we work with, within the communities we serve.

2. It takes time and effort to learn how to speak clearly

We’ve written a lot about how we assess and treat children with unclear speech – and why. In brief, it takes years and thousands of hours of talking for typically developing children to learn to speak like adults. It’s normal for young children to make lots of speech errors as they develop. Most children’s speech clarity and fluency continues to improve even into the later years of primary school.

3. Disordered speech is a concern, but can be treated

Unusually unclear speech – disordered speech – is worth worrying about, and many, good, evidence-based treatments are available and early intervention is often recommended. Speech sound disorders are not that rare: about 10% of children have developmental speech sound disorders (e.g. Bishop, 2010), and there are many other things that can cause or contribute to unclear speech (see below).

4. What do we mean by “intelligible speech”?

“Intelligible”:

- means “able to be understood”(OED 2000); and

- comes from the Latin word “intelligibilis” meaning “that can understand; that can be understood,” from intellegere “to understand, come to know”.

When it comes to speech, intelligibility often means clear enough to be understood by an unfamiliar adult in conversation.

5. At my child’s age, how intelligible should her speech be to unfamiliar adult listeners?

Views differ:

- According to some experts, a child of 3 years or older who is unintelligible is a candidate for speech therapy (Bernthal & Bankson, 1988).

- According to one highly cited study – where parents were asked to rate how much of their child’s speech they believed a stranger would understand in conversation – typically developing children should be:

- 50% intelligible by 22 months of age;

- 75% intelligible by 3 years, 1 month of age; and

- nearly 100% intelligible by 3 years, 11 months of age (Coplan & Gleeson, 1988).

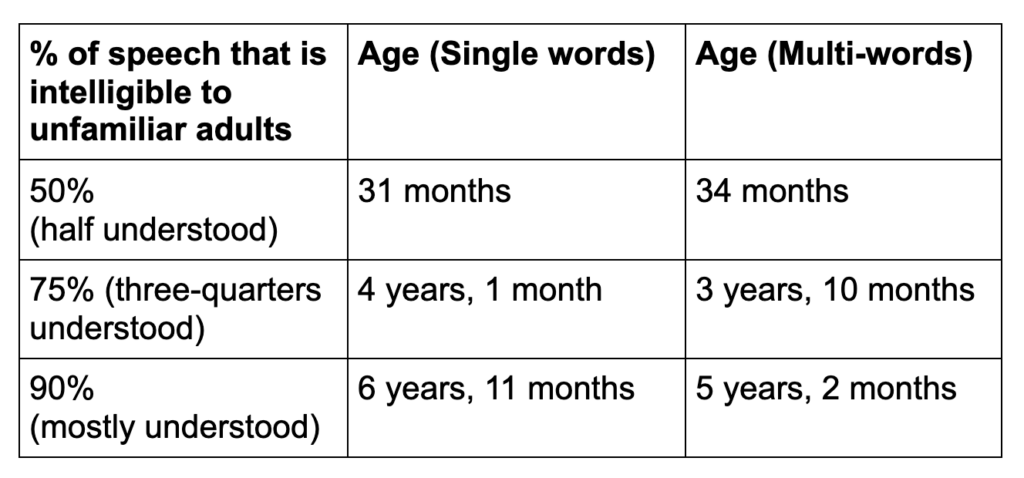

In a recent study (cited and linked below), researchers reported that, on average, typically developing children hit intelligibility milestones objectively later than the parent-estimate studies would suggest, as follows:

The researchers found lots of variability in intelligibility development among typical children. They concluded that, in multiword utterances, children should be at least:

- 50% intelligible to unfamiliar adult listeners by 4 years of age;

- 75% intelligible by 5 years of age, and

- 90% intelligible at just over 7 years of age (Hustad et al., 2021 – see full citation below).

At first glance, these recent findings were surprising. I think many families (and speech pathologists) would be shocked to think that the average, typically-developing child’s speech only becomes 90% intelligible at the word level at the ripe old age of 6 years, 11 months! But, when you look more closely at how the study was conducted, what it set out to measure (and not measure), and its limitations, the findings make more sense and fit better with the wider body of speech pathology research.

6. Beyond lab norms: real world intelligibility matters more

Peer-reviewed intelligibility studies conducted in ideal laboratory conditions like those reported in Hustad et al., 2021 are very helpful. But assessing the intelligibility (or unintelligibility) of an individual child requires us to consider a number of factors in addition to norms.

In some ways, lab tests of intelligibility set the bar higher than we do in clinic or real world settings. For example, in lab studies, speech samples may be audio-recorded only, and may involve speech targets with limited context for the listener.

In other ways, lab tests can be less demanding than in the clinic or in the real world. In lab studies, listeners are usually fully focused on the child’s speech, and the recordings they listen to may be modified to remove background noise and other distractions.

In accent modification studies, researchers distinguish between:

- intelligibility – how understandable speech is when a listener is paying full attention in a controlled environment; and

- comprehensibility – how easy speech is for a listener to understand in the real world, e.g. when you may not be paying full attention to the speaker (e.g. Munro & Derwing, 1995).

This is a useful distinction that could be applied to the discussion of child speech sound disorders. In any event, a child’s speech intelligibility to others in the real world depends on the child’s total communication skills, the listeners’ speech and language skills and experiences, and the environment and context in which the child speaks:

A. Child communication factors

Lots of things can affect a child’s ability to speak clearly. Here are just a few examples:

- A child may have a neuro-developmental disorder, a genetic syndrome (e.g. Down’s syndrome), or a hearing impairment that affects their speech development and/or ability to speak clearly.

- A child may have a physical disability that affects their movement (e.g. cerebral palsy).

- A child may have difficulties planning the movements needed to speak clearly or with appropriate prosody – things like primary stress and intonation (e.g. Childhood Apraxia of Speech).

- A child may have difficulties speaking fluently (e.g. they may stutter or clutter).

- A child may simply not yet be able to produce some speech sounds.

- A child’s speech may contain typical, delayed, and/or unusual speech error patterns or phonological processes, including substituting different sounds and/or leaving sounds out.

- A child may have a Developmental Language Disorder that affects their ability to use spoken words to express their thoughts and feelings clearly. Language disorders can also affect a child’s ability to recall and repeat words and sentences (which can affect their performance on speech tests).

- A child may have suffered a traumatic brain injury that affects their speech, e.g. by causing dysarthria.

- A child may have a voice disorder (e.g. because of reflux or nodules) that makes them hard to understand.

- A child may be learning more than one language – and speech sound system – and/or may speak with an accent that is difficult for people from a different language background or culture to understand easily (note: this is not a disorder).

- A child may be reluctant to speak in one or more environments or be selectively mute.

- A child may grow up in a household where they are unsafe, or may grow up in abject poverty, or in a home with limited speech, language and literacy stimulation.

Hustad and her colleagues set out to study typical children. As such, they were deliberately very selective in who they chose to recruit for their lab study.

All of the 538 children studied had normal speech, language and hearing. All were recruited from one mid-western region of the United States. Almost all the children were white. A very large proportion of children had mothers who had at least one college or university degree (a proxy for high socioeconomic status). It is unclear if any of the children were bilingual or learning English as an additional language. While the sample may have reflected demographics of the community studied, it is very different to the communities we work with.

In the Hustad study, intelligibility was not measured from the child’s speech in natural conversation with an adult. Instead, the children repeated standardised recordings of an adult saying a set list of words and sentences while looking at pictures of the targets on an iPad. Not all children were able to repeat all the test items, probably due to language constraints.

B. Listener factors

Intelligibility is about being understood. If I attempt to speak in English to someone who does not understand the language, I will be unintelligible to them. If they ask me to clarify my meaning in Mandarin Chinese or in Australian Sign Language, they will be unintelligible to me.

If, instead, we both speak English, but I proceed to speak with a broad Australian accent and they reply quickly with a strong Glaswegian accent, we may struggle to understand each other’s speech, even though we share a language.

A child’s intelligibility depends, in part, on who is listening to the child. For example:

- some adults seem to understand young children’s speech more easily than others;

- as you would expect, parents can almost always understand their child’s speech better than adult strangers;

- many health and early education professionals become adept at understanding children’s speech through experience, including working with children with speech sound disorders;

- some adult listeners have hearing, language, learning, and cognitive difficulties themselves; and

- some adult listeners may understand and speak the child’s language as a second (or later) language or may speak a different dialect of the child’s language.

Again, the researchers in the Hustad study had to be selective in who they asked to assess the children’s intelligibility. To qualify, you had to be a normal-hearing adult who: (i) spoke American English natively; (ii) had limited experience listening to children with communication disorders; and (iii) reported no language, learning or cognitive disabilities.

In the real world, lots of people of different abilities and experiences will listen to your child, and their ability to understand your child may vary widely.

C. Language and environmental context

The context in which speech happens can make a big difference to intelligibility. For example:

- In the real world, many children supplement their speech with gestures like pointing, showing, nodding and facial expressions (e.g. to protest or express disgust). If you can’t see a young child’s face or gestures (e.g. on a phone call), their speech is often harder to understand.

- The physical environment we’re interacting in often increases intelligibility. If I am working with an 18-month-old who says /ba/ while pointing to a bubble machine, I am likely to interpret the syllable as an attempt at “bubble”. If she does it while pointing at a sheep at a petting zoo, I will probably interpret it as a reference to a sheep sound (“baa”). In both cases, I think I understand the word attempt even with just a syllable to go on (and even if the child actually meant something completely different). If I hear a recording of /ba/ with no context, I am more likely to interpret it as babble, rather than an early word attempt, and I’m less likely to know what the child meant.

- In the Hustad study, the researchers found that, from the age of around 4 years old until around 10 years of age, children were more intelligible to adult strangers when they spoke in word combinations and sentences, compared to single words. One explanation for this finding was that context allowed listeners to infer missing or distorted speech information compensating for children’s speech errors. (This is one reason children with good oral language but unclear speech often seem more intelligible than children with both DLD and unclear speech.)

- People are harder to understand if there is a lot of background noise or if you are otherwise distracted. Much of our communication with young children outside the clinic happens in noisy and distracting places, like preschools or parks. In the presence of background noise, adults tend to use more gestures and exaggerated facial expressions. We also increase our volume and check for comprehension more often.

- The assessment task can make a big difference to intelligibility. Some children speak more clearly when they repeat an adult model than in spontaneous conversation. This is why naturalistic language sampling tasks like conversation samples and story retelling tasks are such an important part of our assessments of children with suspected speech sound and other communication difficulties.

The Hustad study required the adults to listen to digital audio recordings of standard words and sentences. Background noise was digitally removed and the speech signal was ‘normalised’. The word and sentence lists were presented in random order (although delivered in separate blocks). The listeners heard each word and sentence once only, and then had to type what they thought the child said. Two listeners listened to each child’s samples and their scores were averaged.

In other words, the children’s speech intelligibility was assessed by adults who: (i) did not see the children; (ii) had no environmental context; and (iii) listened to audio recordings that had no background noise or other distractions. In these conditions, I was not surprised that the intelligibility ratings were lower than parent estimates of intelligibility in the real world, and our real world clinical observations of children with and without speech sound disorders.

7. So does the new research mean we shouldn’t worry if no-one understands my 3 or 4 year-old child?

That is not the key takeaway from the new research.

Intelligibility norms are just one factor we think about clinically when we meet a child with unclear speech. We focus on other things, too, including:

A. The functional impact of unclear speech on the child

For example, we look at whether (and if so how) the child’s unclear speech is:

- affecting their participation, e.g. on playdates, at preschool, at home with family members, in sport and other team activities;

- affecting their confidence in communicating their thoughts and feelings and their overall oral language development, including language content, structure and social uses;

- attracting negative social attention, e.g., teasing, bullying or contributing to emotional and behavioural problems, or or labelling and lower expectations from adults (e.g. family members or educators); or

- worrying their parents or other loved ones.

Through clinical practice, I’ve learned that the objective severity of a child’s speech sound disorder does not automatically correlate with the effect it has on their life and the lives of family members. A functional approach is better than a pure impairment-based approach:

B. Risk factors and other communication challenges

We look at known risk factors for communication disorders, like family histories of speech sound disorders, and assess to see if the child has any other communication challenges. For example, if the child has unclear speech and DLD, or unclear speech and stuttering, or unclear speech and reading difficulties, we are more likely to recommend early intervention.

We also look at whether the child has any other health or learning challenges that might be contributing to their communication difficulties or participation.

C. Risks of future communication difficulties

Here, we look at the evidence about the short, medium and long term effects of speech sound disorders. For example, we know that speech sound disorders can affect a child’s school readiness, hamper social participation and relationships with parents, siblings, teachers and schoolmates, contribute to reading and writing difficulties, reduce school success, and lower a child’s overall quality of life (e.g. McCormack et al., 2009).

Ideally, we want a child’s speech to be intelligible to their teachers and peers on their first day of ‘big school’ in light of the school readiness literature. We also know that residual speech sound errors can have ongoing negative social and other effects, even if they don’t get in the way of speech being understood.

8. Bottom line

We are, as always, grateful to be living in a time when so many researchers around the world are doing such clinically useful research into child speech sound disorders. New intelligibility norms help us recognise the variability of intelligibility development among typical children in lab settings.

On balance, the new norms have not changed our general guidance to families in any radical way. If:

- your child is 3 years old (or older) and adults can’t understand most of what they say; or

- your child’s speech is getting negative attention from peers or others; or

- your child is 4 years old and isn’t generally intelligible to unfamiliar adults in real world, face-to-face conversations; or

- a health or early education professional working with your child is concerned about your child’s communication skills; or

- your child is frustrated or upset that others can’t understand them; or

- you are concerned for any other reason about your child’s communication skills or development,

we suggest that you give your local speech pathologist a call for a chat.

Principal source: Hustad, K.C., Mahr, T.J., Natzke, P., and Rathouz, P.J. (2021). Speech Development Between 30 and 119 Months in Typical Children I: Intelligibility Growth Curves for Single-Word and Multiword Productions. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 1-13.

Related articles:

- Important update: In what order and at what age should my child learn to say his/her consonants? FAQs

- FAQ: 10 common speech error patterns seen in children of 3-5 years of age – and when you should be concerned

- Lifting the lid on speech therapy: How we assess and treat children with unclear speech – and why

- My child’s speech is hard to understand. Which therapy approach is appropriate?

- Do you recognise any of these 12 speech-related warning signs that your child might have a hearing problem?

- Childhood Apraxia of Speech: FAQs and treatment update

- How to identify and treat young children with both speech and language disorders

- Parent dilemma: What to do when your child stutters and has speech sound problems – research update

- Why preschoolers with unclear speech are at risk of later reading problems: red flags to seek help

- Is your child ready for school? Focusing on what matters most

- Is your child ready for school? What Kindergarten teachers say

- Beyond flashcards and gluesticks: what to do if you or your 9-25 year old still has speech sound issues

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.