“My toddler doesn’t speak at all!” Don’t panic – get informed

For parents of most toddlers, a moment’s peace is as welcome as the Easter Bunny. But when your two year-old doesn’t speak at all, silence can be very stressful – especially when all the other kids in the family/playground/mothers’ group/daycare centre/soccer tots/park, etc. seem to be talking non-stop.

If your child isn’t saying words at 18 months, most GPs and speech pathologists (including me) will recommend a speech and language assessment. But this can be a big step for some parents and other carers. And you have every right to inform yourself about what is involved.

How do speech pathologists help?

First, we assess your toddler’s communication skills. If there is a clinically significant language or speech delay, we design a therapy plan to help you kick-start your child’s language development.

But my child is too shy/won’t sit still/doesn’t “perform” well for others/may tantrum. Can speech pathologists still help?

Yes. Very few speech pathologists I know advocate sitting a toddler at a table and using flashcard drills etc., to help him/her learn to speak. That’s simply not how early language development works.

And we’re not going to make any fixed determinations based on what your toddler does or doesn’t do on our first meeting! Good speech pathologists will supplement what they see on the day with lots of questions about what you know about your child and how your child responds in different places with different people. Good speech pathologists will adjust their therapy to accommodate your child’s interests, on what they see during the course of therapy and on what you tell them.

So what is the goal of speech-language therapy for toddlers?

Not always first words. At least, not always words first.

To answer this question, we need to step back and cover some basics about typical language development:

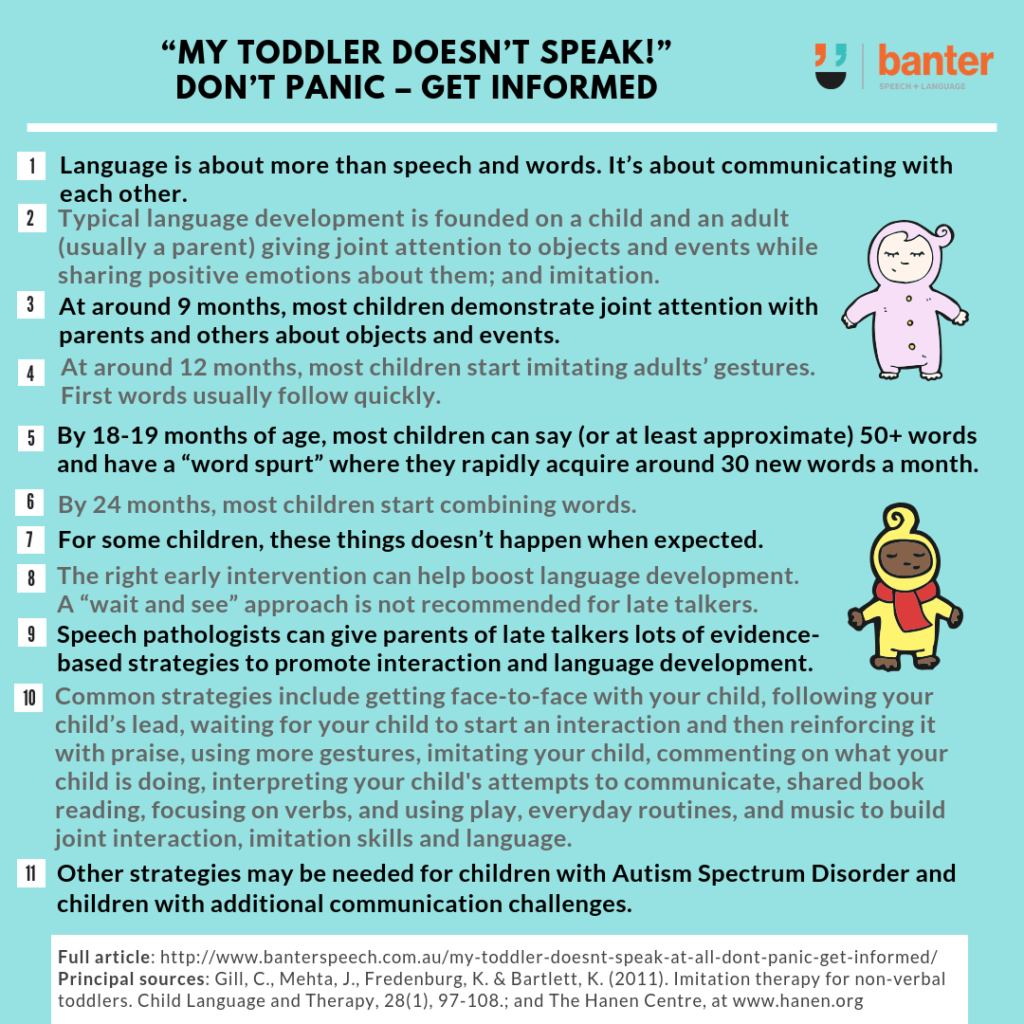

- Language is about more than speech or words. It’s about communicating with each other.

- Typical language development is founded on joint attention (e.g Gill et al., 2011).

- At 12 months, most children start imitating adults’ gestures (e.g. Adamson & Bakeman, 1985). This is often followed in short order by first words (Tomasello et al., 1993).

- By 18-19 months of age:

- most children can say (or at least approximate) 50+ words (Nelson, 1973); and

- most children have a “word spurt” where they rapidly acquire new words (Bloom, 1973) – sometimes over 30 new words each month (Goldfield and Reznick, 1990).

- By 24 months, most children start combining words.

For some children, these things doesn’t happen. There are several known red flags for delayed language development. They include:

- a failure to babble by 12 months;

- a lack of interest in imitating gestures (Hamaguchi, 2001); and

- a lack of a 10-50 word vocabulary at the age of 18 months.

A “wait and see” approach is a risky policy for such children (Hedge and Maul, 2006). Instead, we recommend evidence-based speech-language therapy designed to stimulate and accelerate the development of speech-language skills in order that they are normally attained.

Two examples of evidence-based treatment options for toddlers who don’t talk

(a) It Takes Two to Talk (Hanen)

One approach to toddler speech-language therapy is training parents in how to use evidence-based strategies to promote language development. One well-known program is the Hanen It Takes Two to Talk program. A Hanen-certified speech pathologist trains parents in how to use well-known language stimulation strategies for improving communication, including getting face-to-face with your child and following your child’s lead to promote and increase opportunities for interaction. Some speech pathologists deliver this program to groups of parents. I enjoy delivering this training to one family at a time with the child in the room with us (instant practice!).

(b) Imitation Therapy

Many researchers think that increased shared attention and imitation facilitates language development (e.g. Yoder & Warren, 2001). This is the basis of “Imitation therapy”. Developed in the 1970s by Dr Zedler for toddlers who don’t speak, it’s based on the idea that a child’s language skills can be stimulated by:

- helping the child to be aware of his/her ability to affect others;

- providing opportunities for the child to direct others’ attention and actions; and

- providing opportunities to develop shared attention and adult reinforcement of the child’s actions.

Imitation therapy consists of four stages:

- The adult imitates the child’s actions and speech sounds, at the complete “command” of the child.

- The adult imitates and the child imitates for a brief period.

- The adult imitates, but only behaviours related to voice and movements of the face and speech organs (e.g. the lips, tongue, etc).

- The adult and the child reciprocate imitations of behaviours involving the voice, face and mouth.

Each stage may last a few sessions to several weeks. Although sequenced, the stages may overlap. You may also need to step-back a stage, e.g. if the child shows evidence of stress or anxiety.

In 2011, an imitation therapy study was conducted with 5 non-verbal 18-19 month-old children by Dr Cindy Gill and colleagues at Texas Woman’s University. Following 8-9 weeks of therapy, all five children exhibited significant increases in both the number of vocalisations and variety of speech sounds and demonstrated regular spontaneous verbal imitation. The study had no controls and a small sample of participants, which means the effectiveness of the treatment may be overstated. But the paper does provide promising evidence about the potential of imitation therapy to “jump start” non-verbal children who are not speaking.

Are these kinds of therapy appropriate for all children?

No. For example, children with autism spectrum disorder may benefit more from a different kind of treatment that takes into account the specific social, non-verbal and other communication needs. Other children may benefit from being provided with an Alternative or Augmentative Communication method or device either in addition to other therapies or as a standalone solution. It all depends on the child’s strengths, challenges, interests and needs.

(Editor’s note: Next month, we plan to run through some more alternatives to Hanen and imitation therapies for facilitating early speech and language development, so watch this space!)

Ask questions!

I have a rule in my clinic: parents (or other carers) must not walk out the door with unanswered questions. Now I know some people don’t like to ask questions. Others may not know which questions to ask. That’s OK! It’s one of the main reasons I post so many articles onto this website.

Related articles:

- I want to help my late talker to speak, but I’m stuck at home. What can I do?

- Late talkers: how I choose which words to work on first

- Why I tell parents to point at things to help late talkers to speak

- “He was such a good baby. Never made a sound!” Late babbling as a red flag for potential speech-language delays

- Are language development and motor development related?

- 6 principles we follow when assessing toddlers for language delays and disorders

- Helping toddlers with their first words – mix it up and make them useful

- Late talkers: kick-start language with these verbs

- Does my child have a language disorder? 6 questions speech pathologists should ask before assessment

- How do babies and toddlers choose their first words?

Principal sources:

- Hanen website.

- Gill, C., Mehta, J., Fredenburg, K. & Bartlett, K. (2011). Imitation therapy for non-verbal toddlers. Child Language and Therapy, 28(1), 97-108.

Inspiration: I was encouraged to write this post after coming across a discussion of imitation therapy and the Gill articles in an online forum of fellow speech-language professionals.

Image: http://bit.ly/1UwCIzx

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.