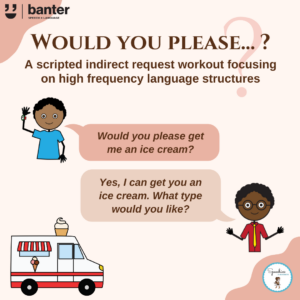

(L269) Would you please… ? A Scripted Indirect Request Language Workout

$5.99 including GST

Between the ages of 36 to 42 months, most typically developing kids start to replace direct requests (like “Give me!”) with indirect requests (like “Can I have..?” or “Would you please…?”). No one knows for sure why we do this – it’s certainly not the most efficient way to ask for things. But so-called “indirect speech” has been studied by linguists, philosophers and speech pathologists for decades (e.g. Grice, 1975; Lakoff, 1973).

Most children pick up indirect request-making skills by around 3 1/2 years of age by watching others. But some students (especially many children with communication difficulties) need some help.

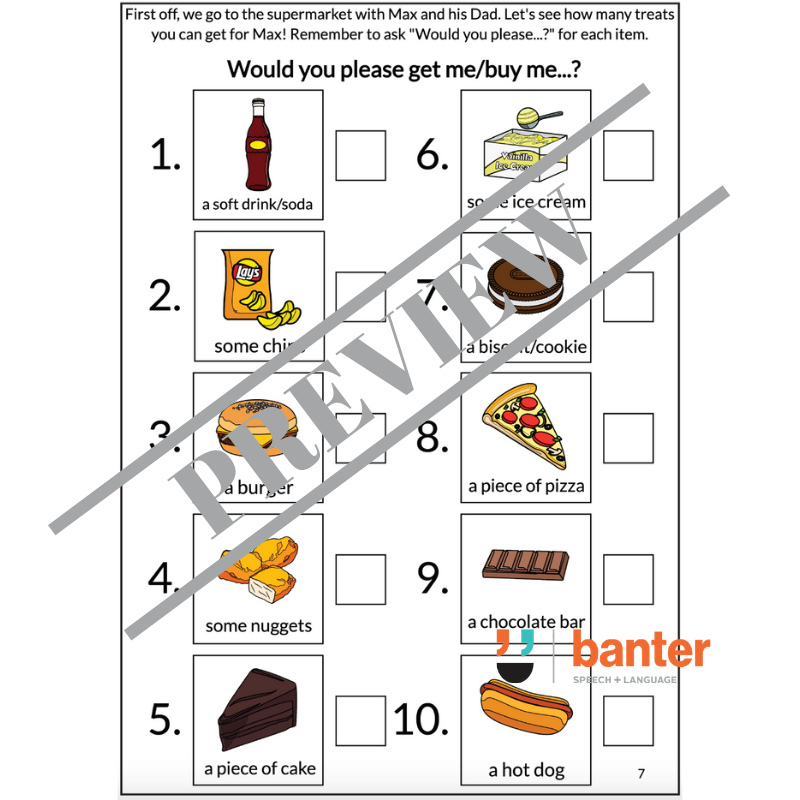

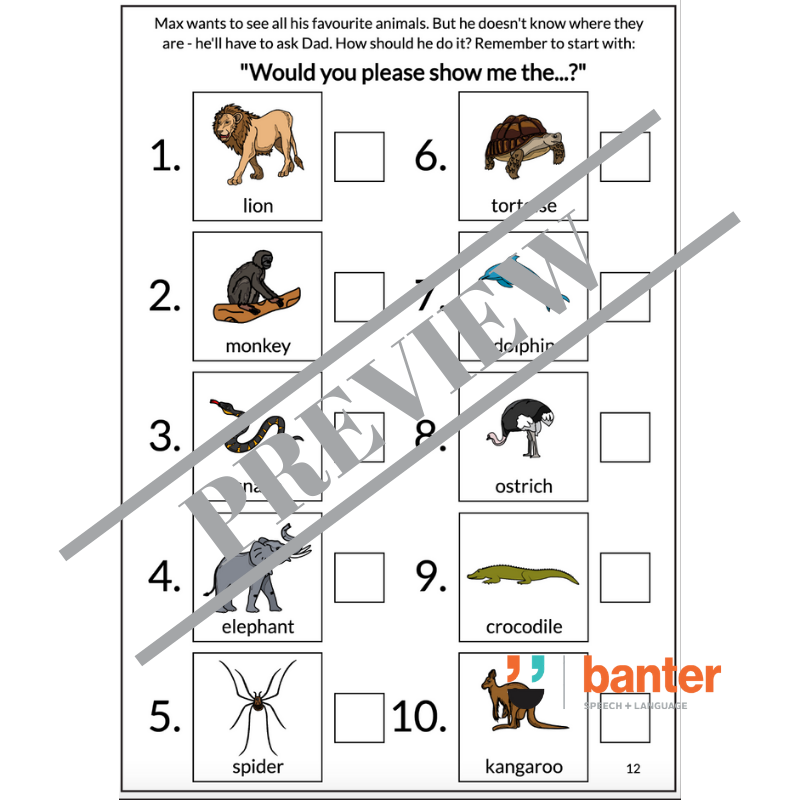

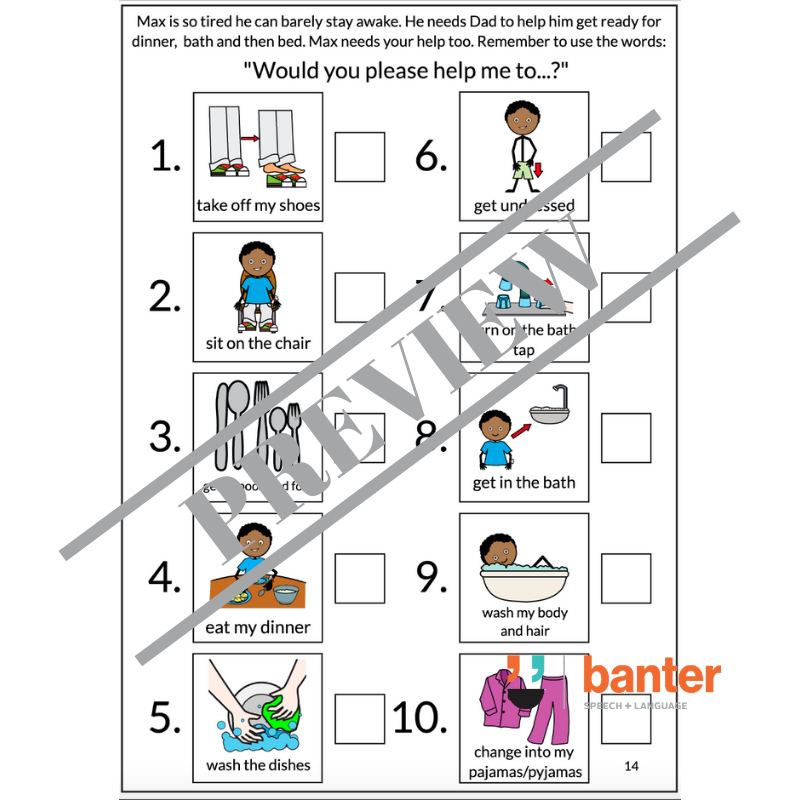

In this resource, we focus on “Would you please…?” as an indirect way to ask for things.

Description

If a toddler screams “Get me chips!”, or “Buy me the dinosaur!”, or “Show me the doll!”, or “Take me to the zoo!”, most adults won’t blink an eye. But if a four year-old – or someone older – does it, we wince and wait for the parent to correct the child.

Why?

Between the ages of 36 to 42 months, most typically developing kids start to replace direct requests (like “Give me!”) with indirect requests (like “Can I have..?” or “Would you please…?”). No one knows for sure why we do this – it’s certainly not the most efficient way to ask for things. But so-called “indirect speech” has been studied by linguists, philosophers and speech pathologists for decades (e.g. Grice, 1975; Lakoff, 1973).

In the 1980s and 1990s, researchers like Brown and Levinson and Clark developed a “theory of politeness” to explain indirect requests. In simple terms, they argued that a speaker’s request for attention or a favour is a ‘social threat’ to the listener’s reputation and authority, which the speaker therefore “softens” with politeness.

Speakers can soften requests to protect listeners from feeling threatened or challenged in several ways:

- Blunt, but polite: “Please help me.”

- Positively polite: “Could you please help me?”

- Negatively polite: “I’m really sorry to bother you, and I wouldn’t usually ask, but do you think it would be possible to help me with this?”

- Fairly indirect: “You are so good at this. I wish someone could have told me that doing it the way you do would help me.”

- Very indirect: “Oh I can’t believe it. I’m probably never going to figure this out.”

In each case, the speaker is asking the listener to help out with a task.

How directly (or indirectly) we ask a listener to help us seems to depend on lots of factors including the size and inconvenience of the favour, the power balance between the listener and speaker, the urgency of the request, and the relationship between the listener and speaker (e.g. you are more likely to use direct requests to ask your sister for a small favour than to ask your boss a big favour).

Why does this all matter?

Some students – including some children with developmental language disorders or social language difficulties – don’t know how to ask for things indirectly. They demand things directly or simply snatch at what they want.

Adult strangers, teachers and even parents are hard-wired to interpret direct requests from 4-year-olds and older kids as rude or insolent: as an affront to good manners. Needless to say, this can lead to these kids being labelled as naughty and immature. Inappropriate direct requests from a 4+ year-old (e.g. “Give me ice-cream!”) can also be embarrassing for families and loved ones who have to endure the judgment of adult strangers in public places.

When to help

Most children pick up indirect request-making skills by around 3 1/2 years of age by watching others. But some students (especially many children with communication difficulties) need some help.

In this resource, we focus on “Would you please…?” as an indirect way to ask for things.

For “Can I please…” sentence structures, check out our companion resource here.

Main source: Lee, J. & Pinker, S. (2010). Rationales for Indirect Speech: The Theory of the Strategic Speaker. Psychological Review, 117(3), 785-807.