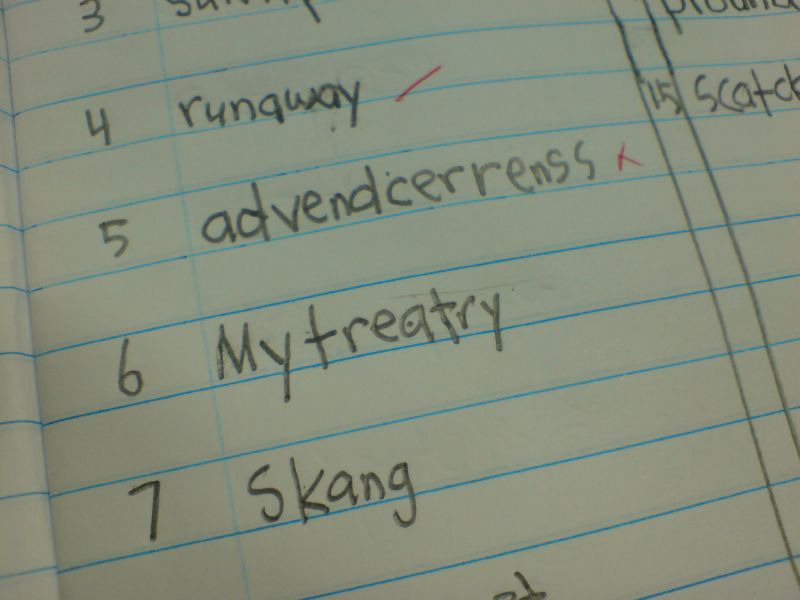

Should we spend time teaching our kids to spell? If so, how, and what should we teach them?

Learning to spell is hard and time-consuming. Should we invest precious school time teaching kids how to spell? I think so. Here’s why:

1. Teachers, bosses and peers judge people who can’t spell negatively

Misspelled words:

-

make writing more difficult to read (Graham et al., 2008); and

-

cause readers to devalue the quality of a writer’s message (Marshall & Powers, 1969).

At school, papers with misspelled words are scored more harshly by teachers for the quality of ideas than the same papers with no spelling errors (Graham et al., 2011). This is consistent with my experience in the corporate and finance sectors: many professionals (me included!) judge spelling errors as a sign of sloppiness and even incompetence – especially in business communications like resumes and business proposals.

2. Spelling problems detract from a person’s writing quality and can reduce motivation to write

For example:

-

if kids have to think hard about how to spell words correctly, they may have less brainpower to expend on the content of what they are writing. They may forget ideas they have yet to write down (Graham et al., 2002);

-

spelling problems can affect a child’s choice of words: they may choose a more general or even incorrect word to describe an object or idea simply because they are unsure of how to spell the more exact word precisely (Graham & Harris, 2005); and

-

kids who are aware that they have spelling problems may avoid writing whenever possible, and become convinced that they “can’t write”, leading to less writing practice and development (Berninger et al., 1991).

3. Learning to spell improves other literacy skills

Learning to spell can improve a child’s:

-

phonological awareness skills, including letter-sound links (Adams, 1990; Conrad, 2008, Ehri, 2005); and

-

word reading (decoding) skills (Graham & Herbert, 2011) and comprehension skills (but not reading fluency skills) (see below).

4. Spelling skills improve more when they are expressly taught to kids than when they are not taught to kids

For decades, researchers have argued about whether spelling should be explicitly taught to kids, or whether it’s better for kids to figure out spelling “naturally”, i.e. without being taught, e.g. from reading lots of stuff and recognising spelling patterns – so-called “statistical learning”. In other words, researchers argue about whether spelling should be “taught” or “caught”.

The weight of good quality, peer-reviewed evidence tells us that:

-

to learn a skill from our environment (e.g. spelling) without being explicitly taught it, we need to pay attention to the to-be-learned material (e.g. Toro et al., 2005). It’s true that kids do learn some spelling patterns from their environment and interests, e.g. how to spell their name. But, for many kids, printed words are simply not attractive enough for them to pay enough attention to spelling as they read. For example, a study showed that, on average, 4 year olds spent only around 5% of the time paying attention to written words when being read to by parents, with the majority of their time spent looking at the pictures (e.g. Evans & Saint-Aubin, 2005; Justice et al., 2008). This is not surprising: unlike with speech, humans did not evolve to pay attention to writing (Treiman, 2018); and

-

the best way to improve a child’s performance on a skill such as spelling, is to focus on the skill directly. In other words, to improve spelling, you need to practice spelling (and not other skills, such as working memory or pattern recognition) (Smith et al., 2015; McArthur & Castles, 2017; Treiman, 2018);

-

children learn to spell more efficiently and effectively when they receive systematic instruction about spelling than when they do not. A major meta-analysis of peer-reviewed spelling studies showed that direct and systematic spelling instruction:

-

improves students’ spelling skills by slightly more than one-half of a standard deviation, across a range of ages/years of school (from Kindergarten to Year 10!);

-

results in long-term gains;

-

results in gains that transfer to students’ performance in some writing tasks; and

-

improves phonological awareness and reading skills, including word reading and comprehension skills (but – interestingly – not fluency) (Graham & Santangelo, 2014).

-

5. Components of effective spelling programs

Spelling programs come in many shapes and sizes, ranging from practising lists of spelling words, to teaching specific spelling skills, to more sophisticated programs targeting a range of spelling skills. Consistent with our approach to literacy teaching and the weight of peer-reviewed evidence, we favour a phonics-based approach to teaching spelling, combined with phonological and morphological awareness training. This includes teaching students:

-

basic letter-sound links;

-

phonological awareness skills like blending sounds most often linked to letters to form words (and segmenting words into sounds);

-

links between combinations of letters and different speech sounds, e.g. “sh”, “ee”, “ou”, “ow”, “ai”, “ay”, “oi,”, “oy”, “oa”, “er”, “ir”, “ur”, “wor”, “ear”, “au”, “ck”, “ng”, “ch”, “ph”, and “ough”;

-

common spelling probabilities and patterns, including context rules (sometimes referred to as “graphotactics”), such as:

-

English words rarely ending in the letters “i”, “v” or “u” (hence “spy”, “love”, “have”, and “blue”);

-

“ck” being used to signify /k/ after a short vowel (hence “black” and “kicking”);

-

“ll” and “ff” being used to signify /l/ and /f/ after a short vowel in stressed syllables (hence “full” and “biff”);

-

vowel letters at the end of open syllables signifying a long vowel sound (hence “navy”, “be”, “I”, “no” and “music”);

-

using a silent “e” at the end of a word to signify a long vowel (hence “like” and “mate”); and

-

“c” signifying a /s/ sound when followed by “i”, “e” or “y” (hence “circle”, “ceiling” and “cycle”);

-

- syllable segmentation tactics (recognising that, usually, each syllable in English contains at least one vowel sound); and

- morphological awareness skills such as the meanings of common:

-

prefixes, e.g. “un”, “dis”, “super”, “sub”, “pro”, “pre”, “con”, “trans”, “ex”, “in”, “uni”, “bi”, “tri”, “quad” and “bene”; and

-

suffixes, e.g. “s”, “es”, “ed”, “ing”, “er”, “est”, “ful”, “less”, “able”, “ous”, and “ness”; and

-

common word roots.

-

While the purpose of this article is not to promote any specific spelling program, we use a range of spelling and word attack programs in our clinic, including Spelfabet, Spalding and Yoshimoto’s morphological awareness programs. We’re also fans of Sounds-Write and other phonics-based programs that aim to teach kids to read through writing.

Clinical bottom line

Kids should be taught to spell because:

-

it improves their spelling, phonological awareness and some reading skills; and

-

poor spelling skills can affect academic and work achievements.

Kids can learn spelling skills through reading/exposure to print – through statistical learning – but progress depends on how much attention they pay to spelling when reading. Many kids don’t pay much attention to spelling patterns when they read.

Structured spelling instruction is more effective and efficient than statistical learning. Spelling programs that focus directly on spelling are more likely to benefit spelling than interventions that focus on other skills, such as working memory or pattern recognition.

Related articles:

- For students with spelling difficulties, where should we start?

- When assessing Kindergarten and Year 1 students for reading difficulties, we should always test spelling. Here’s why

- Is your child struggling to read? Here’s what works

- Kick-start your child’s language with speech sound knowledge (phonological awareness)

- “I don’t understand what I’m reading” – reading comprehension problems (and what to do about them)

- The forgotten reading skill: fluency, and why it matters

- What else helps struggling readers? The evidence for “morphological awareness” training

- Why is English spelling so hard? Why and how should we teach it?

- 24 practical ways to help school-aged children cope with language and reading problems at school and home

- 6 strategies to improve your child’s reading comprehension and how to put them into practice

Principal references:

-

Graham, S. & Santangelo. (2014). Does Spelling instruction make students better spellers, readers, and writers? A meta-analytic review. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 27, 1703-1743.

-

Treiman, R. (2018). Statistical Learning and Spelling. Language, Speech, and Hearing in Schools, 49, 644-652.

Image: https://tinyurl.com/yd8ft2mz

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.