Teaching the alphabet to your child? Here’s what you need to know

1. Letter names are not the same as speech sounds

In English:

- writing takes the form of a sound-based, alphabetic code. The letters we use are to a large extent determined by how words sound;

- letters of the alphabet have names (e.g. “a”, “b” and “c”, which we pronounce as “ay”, “bee” and “see”, respectively);

- each letter is linked to at least one sound. The letter “b” (pronounced “bee”) says one sound: /b/ as in the first sound in ball. The letter “c” says one of two sounds depending on the vowel that follows it: /k/ as in “cat” or “cut” and /s/ as in “ceiling”, “circle” or “cycle”. The letter “a” says three sounds: /ae/ as in “apple”, /ei/ as in “gave”, and /a/ as in “father”; and

- the name of each letter is not the same as the sound(s) it makes. For example, we say “aytch” for the name of the letter “h”. But, when we read “h” aloud in a word, we say a “huffy” sound at the back of our throats, /h/. It’s the first sound in “hippo” or “helicopter”. The sound is not “aytch”.

2. To read, speech sounds are more important than letter names

- To read, we need to “decode” the letters, turn them into speech sounds, and then blend them together to say words.

- Unfortunately, most of us learn the alphabet from the “Alphabet Song” (Smith, 2000) or from early learning books that focus on the letter names.

- For example, kids learn to say the letter names “See” (for “c”), “Eff” (for “f”), “Jee” (for “g”), and “Ex” (for “x”), rather than the sound(s) they make, namely:

- /k/ as in “cat” or /s/ as in “ceiling”;

- /f/ as in “fire”;

- /g/ as in “goat” or /d ʒ/ as in “giraffe”; and

- /ks/ as in the sound at the end of “fox”.

- Understandably, this confuses kids (and everyone else!):

- Some kids memorise the Alphabet Song but can’t recognise letters in isolation. For example, they may think that “l-m-n-o-p” is one name (very common), or they may be able to recite the letters in order, but can’t tell you what letter comes after “s”, or before “d”.

- If kids try to use letter names (rather than sounds) to read the word “cat”, for example, they end up with “seeaytee”, rather than /kaet/.

- Therefore, when teaching your child a letter, stress the sound(s) that the letter makes. For example:

- “This is the letter “k” [pronounced “kay”]. It says /k/ [not “kuh”], as in “koala” or “kangaroo”.

- Tip: When teaching short “plosive” sounds, like /p, b, d, t, k, g/ do not add an “uh” to the end of the sound – it’s /p/, not “puh”; /t/, not “tuh”; and so on. Otherwise, you end up with the child saying “kuhat” for “cat”.

3. But letter names are not irrelevant!

- Alphabet knowledge is an important emergent literacy skill (e.g. Hammill, 2004).

- Knowledge of letter names in Kindergarten is one of the strongest predictors of future reading ability (e.g. Catts et al., 2002).

- Poor alphabet recognition skills is a risk factor in later reading difficulties (Catts et al., 2001).

4. To help with reading, link letter names to the sounds they make and teach them together

- To understand the alphabet, children must not only be familiar with the letters, but they must be able to identify and manipulate the sounds to which the letters are linked (Neilson, 2003).

- In other words, we need to explicitly, deliberately teach children the links between letters and sounds.

5. Lower case letters are more important than uppercase letters

- Lots of research seems to have focused on the ability of kids to read upper-case (CAPITALISED) letters (e.g. Ellefson et al., 2009).

- But the ability to recognise lower-case (uncapitalised) letters is critical for reading: most of what we read is made up of lower-case letters (Worden & Boettccher, 1990). Lower-case letters are used around 17 times more often than capitalised letters.

6. In what order should I teach my child the letters of the alphabet?

- Start with the letters in your child’s name. Pre-schoolers and Kindergarten kids are usually better able to recognise the first letter of their name than other letters (e.g. Justice et al., 2006). There’s also some evidence that this “own-name” advantage extends to other letters in the child’s name (e.g. Treiman et al., 2006).

- Teach letters in the order kids learn to say the speech sounds linked to the letter (Lehr, 2000) (see below for a system based on this idea).

- Teach the letters where the upper-case and lower-case versions of the letters look similar. Treiman & Kessler (2004) identified nine such letters:

- Cc

- Kk

- Oo

- Pp

- Ss

- Vv

- Ww

- Xx

- Zz.

- (Note: apparently, this doesn’t work for the letter Uu (Evans, 2006)).

- Don’t teach letters at the same time that are easily confused. This includes:

- letter pairs that look similar, like:

- b and d;

- p and q;

- m and w; and

- v and u (Evans, 2006); and

- letters where the letter names (when said out loud) include similar sounds, e.g.

- b, p, d, e (which are said as “bee”, “see”, “pee”, “dee” and “ee”); and

- a and h (which are said as “ay” and “aytch”) (Treiman & Kessler, 2003).

- It’s tricky to avoid this problem: only six letter names are phonologically distinct: e, o, i, r, u, y (Huang & Invernizzi, 2014), and it’s debatable whether “e” and “y” are truly distinct.

- letter pairs that look similar, like:

7. Is there an “ideal” order in which you should teach your child the alphabet?

No.

But there are a couple of researchers and publishers who have given it a go, based on one or more principles set out above:

A. Lehr (2000) (lower-case, based principally on the order of speech-sound acquisition in children):

Pre-school kids: n, w, p, h, m, a, b, k, d, f, o, c, e, y, g, t, s, r, z, i, q, v, l, u, j, x

Kindergarten kids: m, t, f, n, h, a, p, z, b, i, s, d, u, v, l, w, o, r, g, e, j, c, k, y, q, x

B. Carnine, Silbert & Kame’enui (1997) (lower- and upper-case)

a, m, t, s, i, f, d, r, o, g, l, h, u, c, b, n, k, v, e, w, j, p, y, T, L, M, F, D, I, N, A, R, H, G, B, x, q, z, J, E, Q

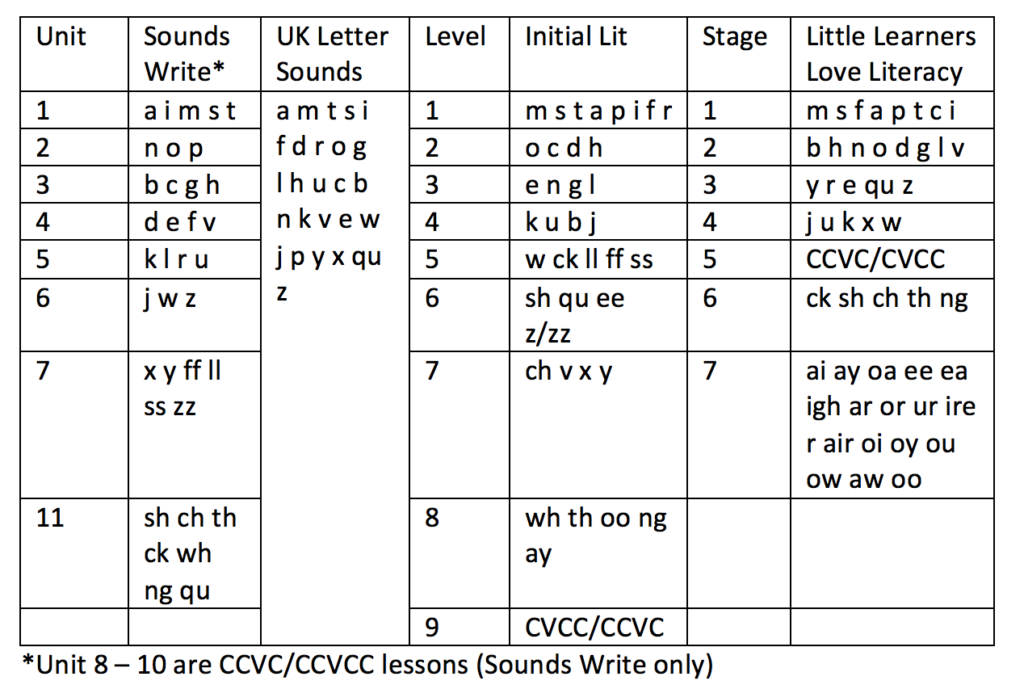

C. Sounds Write, UK Letter Sounds, Initial Lit, Little Learners Love Literacy

Bottom line

For reading and spelling:

- learning the names of the letters of the alphabet is important;

- learning the speech sounds that letters make is more important; and

- linking speech sounds to letters, and blending the sounds together to “decode” writing is most important.

Lots of factors affect how children learn to recognise letter names. However, some factors matter more than others, including:

- whether the letters are in a child’s name;

- the visual similarity of a letter’s upper- and lower-cases; and

- how different a letter looks and sounds to other letters.

Many pre-schools and kindergartens teach a “letter of the week” (e.g. Pressley et al., 1996). But there may be more efficient ways of teaching children letters and linking them to their speech sounds following the principles and sequences outlined above (e.g. Treiman, 2000).

For more about preparing preschoolers to read at primary school, check out our free guide:

Related articles:

- Getting ready to read at big school: a free guide for families with preschoolers

- Is your child struggling to read? Here’s what works

- FAQ: In what order and at what age should my child have learned his/her speech sound consonants?

- Why is English spelling so hard? Why and how should we teach it?

Principal sources:

- Huang, F.L. & Invernizzi, M.A. (2014). Factors associated with lowercase alphabet naming in kindergarteners. Applied Psycholinguistics, 35, 943-968.

- Lehr, F. R. (2000). The Sequence of Speech-Sound Acquisition in the Letter People Programs. Waterbury, CT: Abrams & Company

Image: http://tinyurl.com/zlpmm38

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.