Thumb and finger sucking: facts and treatment options

At dinner with friends a few weeks ago, I was asked about thumb and finger sucking – and how to help kids break the habit.

As luck would have it, a systematic review of treatments was published in 2015 by one of my favourite independent research centres, the Cochrane Collaboration.

So what works?

First some facts

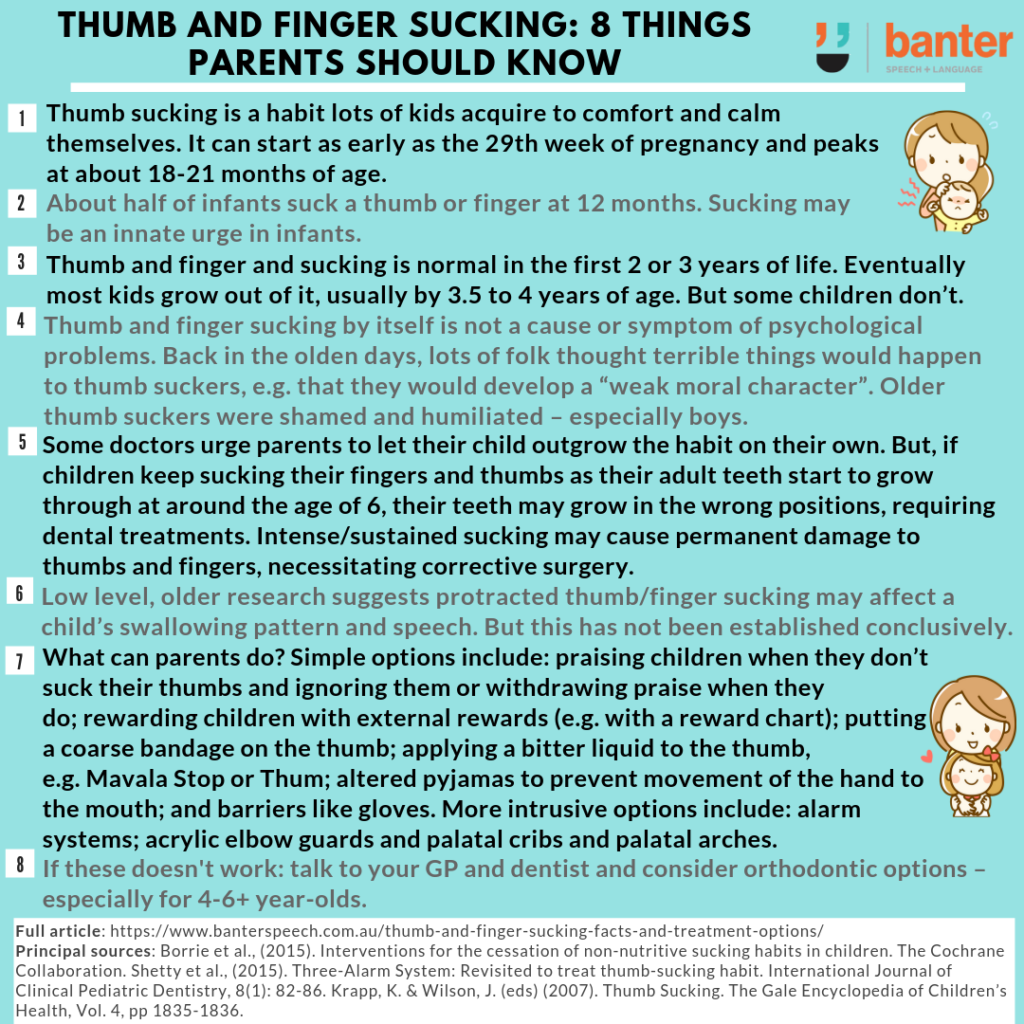

- Like dummy use, thumb sucking is a habit lots of kids acquire to comfort and calm themselves.

- Thumb sucking can start as early as the 29th week of pregnancy and peaks at about 18-21 months of age (Rosenberg, 1995).

- About 50% of infants at 12 months of age suck a thumb or finger (Fukuta et al., 1996).

- Thumb and finger and sucking is considered normal in the first 2 or 3 years of life. Eventually most children grow out of the habit, or stop due to the “encouragement” of their parents usually by 3.5 to 4 years of age (Shetty et al., 2015); and the average age for spontaneous cessation of the habit is 3.8 years of age (Fukuta et al., 1996).

- Some children don’t grow out of it by 4 years.

Why does it happen?

We don’t know. There two main theories:

- The emotional theory: Freud and his followers proposed that digit sucking was related to the so-called oral phase of child development and thought that, if it went beyond the oral phase, it could develop into a fixation (a sign of emotional disturbance).

- The learned behaviour theory suggests that sucking is an innate urge in infants and that finger sucking is an outlet for an excess sucking urge when breast or bottle feeding is quickly and efficiently achieved (e.g. Johnson & Larson, 1993).

Learned behaviour theory is currently the more popular explanation (e.g. Shetty et al., 2015). Most researchers now accept that thumb and finger sucking by itself is not a cause or symptom of psychological problems or insecurity (Krapp & Wilson, 2007).

What happens if children don’t break the habit by 4 years of age? Opinions and evidence

a. Opinions

Back in the olden days, lots of folk – including some 19th century doctors and German children’s book writers – thought a whole host of terrible things would happen to thumb suckers, e.g. that the child would develop a “weak moral character” which would damage them for the rest of their lives. Parents were advised to break the habit, sometimes forcibly. Parents were sometimes told to put mechanical restraints on their children’s hands, coat thumbs with bitter substances or rough tape, or to use gloves. It was also considered necessary to shame and humiliate the thumb sucker – especially if he were a boy (Krapp & Wilson, 2007). (As an aside, this is thought to be one reason why more girls than boys suck their fingers after the age of 4 years.)

This 19th century German story book solution is not recommended!

Perhaps in reaction to the rather extreme views of earlier thinkers, some modern doctors and others urge parents to let their child outgrow the habit on their own. Some think thumb sucking is more of a problem for the parent than the child and that putting too much pressure on the child to drop the habit may backfire and actually prolong thumb sucking.

Both these positions are of course just opinions.

b. Clinical research evidence

- If children continue to suck their fingers and thumbs as their adult teeth start to grow through (around the age of 6), there is a risk the teeth will grow in the wrong position causing them to stick out too far or not meet properly when biting. These children often need dental treatments to fix problems caused by their sucking habit (Borrie et al., 2015).

- In some cases, intense and sustained finger sucking may cause permanent damage to thumbs and fingers, necessitating corrective surgery (Shetty et al., 2015).

- There is very low level, relatively aged, evidence suggesting that protracted thumb and finger sucking may affect a child’s swallowing pattern and speech (e.g. Norton & Gellin, 1968). But – just like with dummy use – this has not been established conclusively.

What can parents do to help children break the habit?

Popular simple options include:

- praising children when they don’t suck their thumb (intrinsic rewards) and ignoring them or withdrawing praise when they do;

- rewarding children with external rewards (e.g. with a sticker reward chart requiring a certain number of”sucking free day” stickers to get a reward like iPad time or a small toy);

- putting a coarse bandage on the thumb;

- applying a bitter over-the-counter liquid to the thumb, e.g. Mavala Stop or Thum;

- (if it only happens at night) altered pyjamas to prevent the movement of the hand to the mouth; and

- barriers like gloves.

More intrusive options for more mature children include:

- a three-alarm system developed by Norton & Gellin in the late 1960s. A chart is designed with the days of the week and blank spaces. During the day, when the habit normally happens, the child’s thumb/finger is wrapped in a coarse adhesive tape. When the child feels the tape in his/her mouth, this is the “first alarm” to stop, and the elbow is then wrapped firmly (but not too tightly!) with an elastic bandage with a closed safety pin at the elbow and at each end. The “mild jabbing” acts as the second alarm to stop sucking, after which the bandage is tightened further for a short time;

- a modified three-alarm system developed by Shetty and colleagues with an acrylic elbow guard fitted with a chip that plays music whenever it is bent used instead of a bandage (Shetty et al., 2015); and

- the fitting of an orthodontic appliance like a palatal crib or palatal arch.

All of these options have pros and cons. For example, bandages can cause infection, sweating and reduce blood circulation. Kids can adapt to bitter solutions. Altered pyjamas can cause increased wakefulness/sleep problems. Three-alarm systems can also cause embarrassment, discomfort and (with pins) injury. Orthodontic options can damage tooth enamel and cause gum problems (and can always be taken out).

There is low level clinical research evidence supporting two kinds of treatment:

- giving advice and incentives for changing behaviour – either as a standalone therapy or coupled with applying a bitter-tasting substance to the child’s thumbs and fingers; and

- the use of two different kinds of braces in the mouth – palatal cribs and palatal arches – to make it physically difficult for the child to continue the habit (Borrie et al., 2015).

There is as yet no evidence that one of these options produces materially better results than the other. Evidence from one study suggests that, of brace options, palatal cribs are more effective than palatal arches.

Note that the quality of the evidence for all these treatments is fairly low because of the small number of children studied and the high risk of bias in each of the studies reviewed.

So what would I do?

As a speech pathologist, and in the absence of compelling evidence for one type of treatment over another:

- I’m drawn to behavioural treatments as the first option, especially with younger children. My experience with administering behavioural treatments for communication disorders (e.g. the Lidcombe Program for stuttering or the Cycles treatment for severe speech sound disorders), has taught me that focusing on rewarding behaviours we want and withholding rewards for behaviours we don’t want can have a powerful effect on motivating children to change behaviours without the need for special equipment or “punishments”.

- I would first explain to the child why thumb/finger sucking is “yucky”, e.g. “it will wreck your teeth, which will make you look snaggle-toothed, and you might get sick with all those germs from your thumb/fingers”. I might even put up a poster about how only babies suck their thumbs/fingers, with (cute – not terrifying!) pictures of “yucky germs” and snaggle-toothed thumb suckers contrasted with big kids with great teeth.

- I would then institute a reward sticker chart for the “big girl” or “big boy” and give the child heaps of praise, positive comments and stickers when they didn’t suck their thumb/fingers. If the child continued to suck their thumb, I would simply withdraw the rewards and tell them I was disappointed. I would not punish or shame them publicly – I would simply withdraw praise, express disappointment, and remind them about how babyish and germy the behaviour is. I would also point to the reward chart and perhaps withdraw a point (or two).

- If necessary – if the behaviour continues – I would add a bitter-tasting substance or bandage to the child’s thumb/finger, being careful not to overdo it.

- If, after giving the reward chart/praise strategy a real go for a few weeks (with or without the bandage and bitter solution “add on”), the thumb sucking persisted, I would talk to my child’s GP and dentist and consider orthodontic options – especially for children older than four years who might be at risk of permanent dental issues.

Principal sources:

- Borrie et al., (2015). Interventions for the cessation of non-nutritive sucking habits in children. The Cochrane Collaboration. Full report available here.

- Shetty et al., (2015). Three-Alarm System: Revisited to treat thumb-sucking habit. International Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry, 8(1): 82-86.

- Krapp, K. & Wilson, J. (eds) (2007). Thumb Sucking. The Gale Encyclopedia of Children’s Health, Vol. 4, pp 1835-1836.

Images: http://bit.ly/1U5kuUw and http://bit.ly/1U5m211.

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.