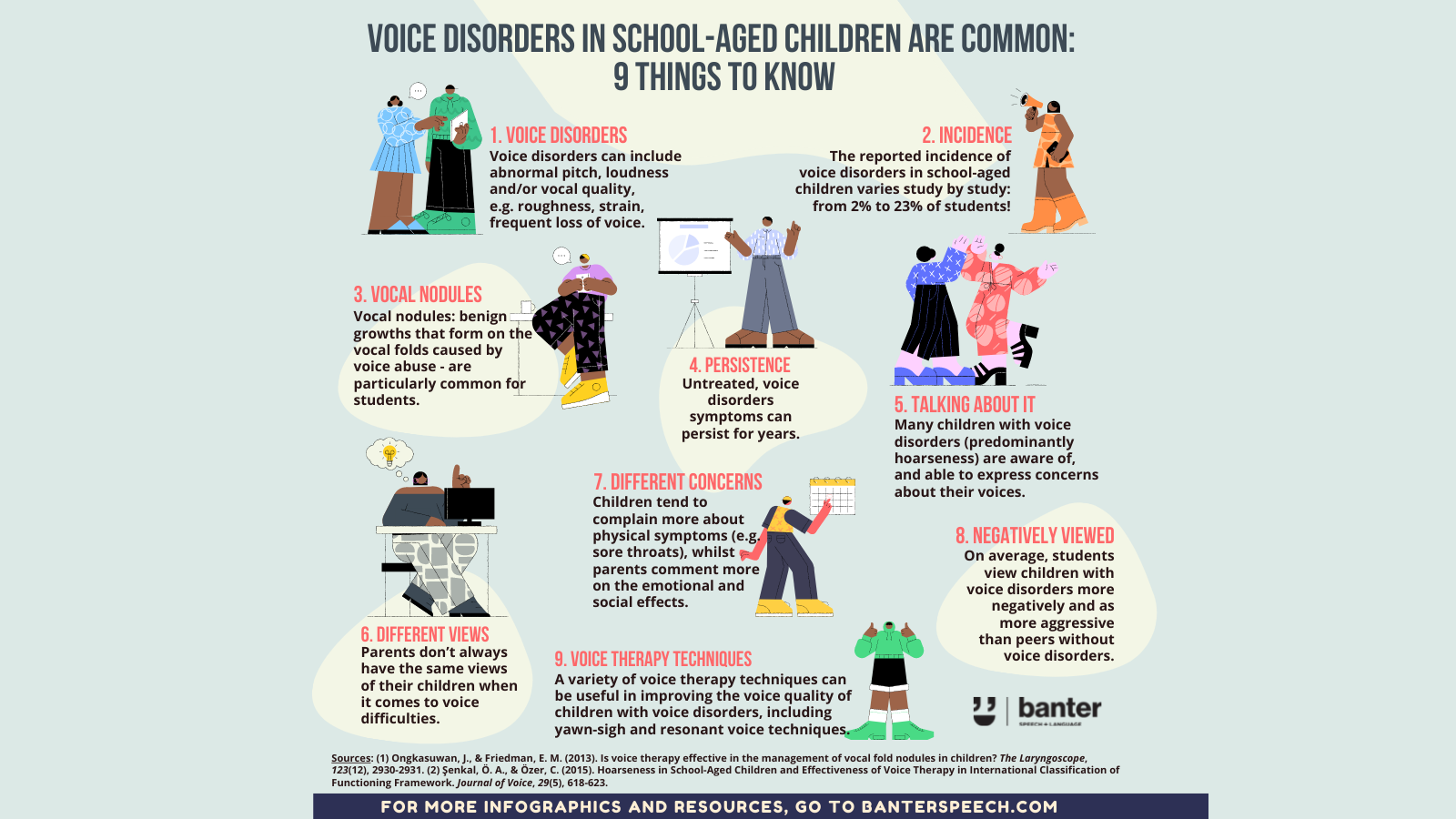

Voice therapy for kids who like to talk and talk. When “vocal rest” isn’t an option

Isn’t it great when voice professionals (including Ear, Nose and Throat Specialists (ENTs) and speech pathologists) give parents really helpful suggestions like “Tell Jimmy not to yell so much”, or “I know Bella loves to talk and sing all day – but she needs to stop, just for for a month or two!”

Traditionally, voice therapy for kids with nodules and other common voice problems caused by excessive shouting or talking has been based on “vocal conservation” or what some have dubbed as “a vocal diet”. For some children, silence – though golden – is not an option: it’s not who they are and they simply won’t do it.

To be honest, there doesn’t seem to be much evidence to support vocal rest as an effective treatment for children. In fact, recent research on other tissue damage suggests that light exercise may actually be better for healing damaged tissue than total rest.

From a speech-language perspective, we don’t want to suppress spontaneous communication and social interaction if we can avoid it. Nor do we want to shame (or bribe) kids into silence unless we’re sure there’s no better, more natural way of helping them with their voices.

After an ENT has ruled out potentially dangerous conditions like Recurrent Respiratory Papilloma and diagnosed a child as having a voice disorder caused by vocal misuse, there are two main ways speech pathologists treat children for voice disorders:

- direct voice therapy, where we work on the child’s voice directly; and

- indirect voice therapy, also known by the dreadful term “vocal hygiene”, where we work with the family to change the child’s environment (e.g. reducing background noise, exposure to smoke), and non-vocal behaviours (e.g. diets, sleep, coughing) to improve the child’s voice. We’ve posted 10 indirect voice therapy tips here.

The goals of direct voice therapy will, of course, depend on what’s wrong with a child’s voice – their voice assessment results. In most cases, however, parents will want their child to end therapy with a clear voice that is:

- loud enough to be heard in a variety of places the child goes, e.g. the classroom, the playground, and the sportsfield;

- not strained or effortful;

- not likely to fatigue quickly; and

- unlikely to cause further damage or trauma to the voice box.

Speech pathologists, who are trained in the anatomy and the use (and abuse) of the larynx (or voice box), know that, to achieve these goals, children need to learn a safe way of producing a relatively loud voice while not banging their vocal cords together, contracting their so-called “false vocal cords”, or allowing too much air pressure to build up beneath their vocal cords when they use their voices. Children need to be taught how to bring their vocal cords together lightly without banging them shut when they speak (or yell). There are a few ways of doing this, including using Voicecraft techniques and principles of Resonant Voice.

While speech pathologists need to understand the anatomy of the voice box and evidence-based treatment options, they also need to earn the child’s trust, help motivate the child to do the therapy and measure the outcomes objectively in collaboration with the family. Each of these elements is an essential part of good voice therapy for children.

Related articles:

- Indirect voice therapy: 10 practical things you can do to help your child achieve and keep a healthy voice

- My child has a voice problem. So what?

- Child voice therapy – an introduction

Key source: Verdolini Abbott, K. (2013). Some Guiding Principles in Emerging Models of Voice Therapy for Children. Seminars in Speech and Language, 32(2), 80-93.

Image: http://tinyurl.com/m5autkm

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.