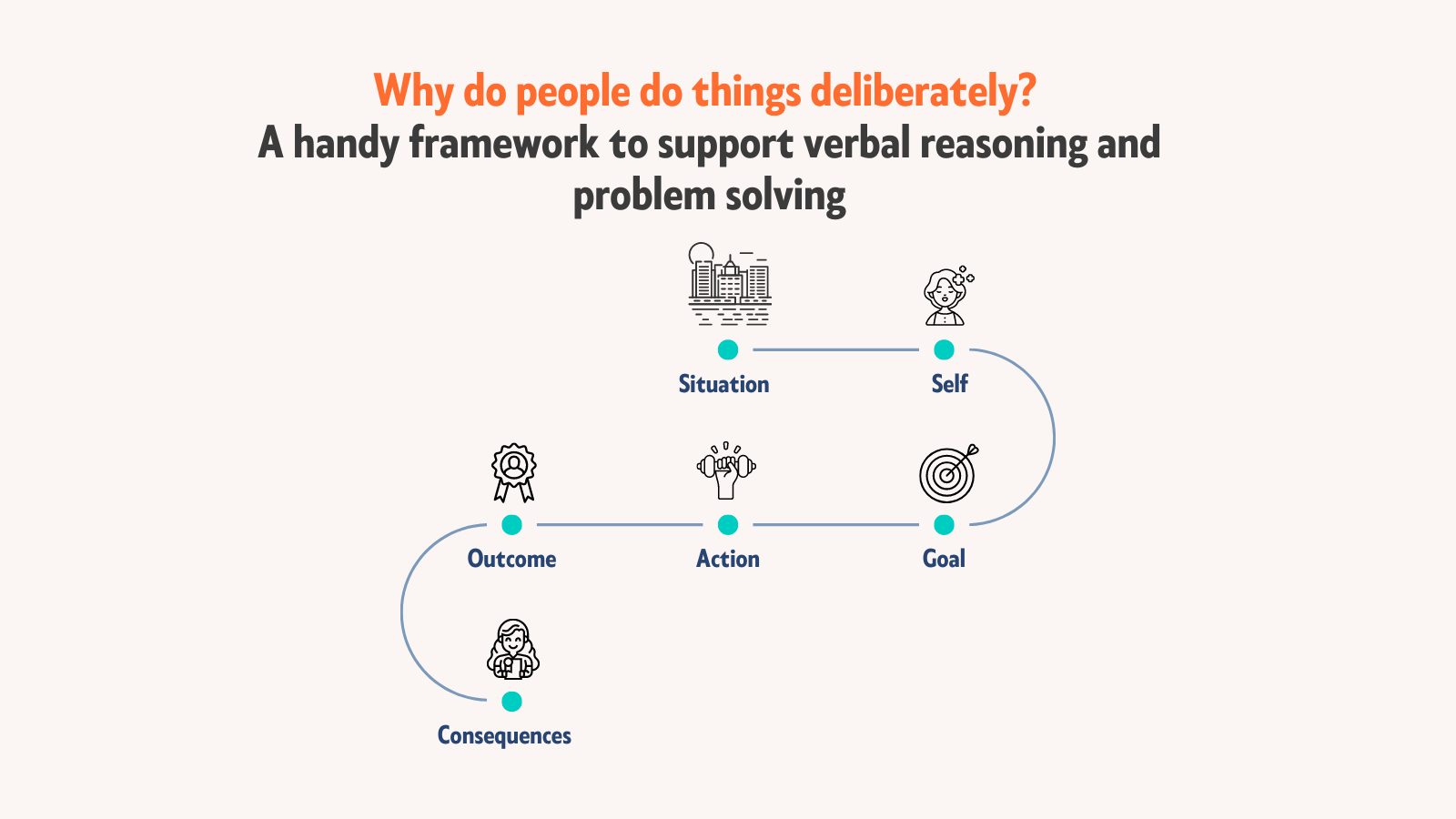

Why do people do things deliberately? (A handy framework to support verbal reasoning and problem solving)

There are many academic theories that seek to describe, explain and predict people’s intentional behaviours. But most of them include the following basic elements:

Source: Urhahne & Wijnia (2023)

Seen this way, a person’s behaviour arises from (two way) interactions between the person and their environment. These interactions stimulate the person’s motives, needs, wishes, and emotions, and result in the person generating a goal to take action. That goal is then translated into an action when opportunity permits. After the action is carried out, the person observes or experiences the action’s outcomes and assesses whether the goal has been achieved. The outcome of the action leads to consequences, which may or may not be intended by the person.

To understand the model further, it helps to know that:

- ‘Situation’ means the social, cultural and environmental context in which the action takes place.

- ‘Self’ is the person: an active agent that translates the person’s needs, motives, feelings, values and beliefs into actions. The concept is connected to ideas of self-efficacy, self-determination, and self-regulation, which do not accept that voluntary behaviours are controlled by outside forces.

- ‘Goal‘ contains the person’s idea of an action’s anticipated incentives and consequences. Goals are intentional (rather than impulsive) and guide the person’s behaviour. But people are not always conscious or aware of all the influences on their goals.

- ‘Action’ is carried up to either pursue a positive event or avoid a negative one for the person. Actions are not always visible to observers.

- ‘Outcome’ is the result of an individual’s behaviour. It can be physical, affective (e.g. a change of mood), or social. When positive, an outcome can be connected to feelings of self-worth and accomplishment.

- ‘Consequences’ often depend on how all people affected by the action evaluate the outcome. When positive, they are often accompanied by extrinsic values, like authority, prestige, promotion or recognition. Consequences can open up new opportunities (or threats) for the person that result in new action sequences.

Example:

| Situation: Daniel’s mid-year English exam is scheduled for 9am tomorrow. Daniel knows his parents and teachers all want him to do well. Self: Daniel also wants to do well, and knows that a good mark will put him in an excellent position to move up an English class next year. He really wants to top the class in the exam, but knows it won’t be easy. Goal: Daniel decides he wants to spend the afternoon studying for the exam so he can do well. Action: Daniel studies for three hours for the exam. Outcome: The next day, Daniel sits the exam. He finds it straightforward, feels good about his performance, and enjoys a sense of accomplishment. Consequences: When the marks are released two weeks later, Daniel comes second in the class. Even though Daniel is a bit disappointed that he did not top the class, his teacher and his parents are both very happy for him. The teacher suggests that Daniel is in with a good chance of moving up a class next year if he keeps up the good work and does as well in the final exam. New Situation/Self/Goal: Daniel is even more motivated to get into the top class. He decides to start studying for the final English test, even though it is more than a term away. |

How this framework can help people with DLD and other communication disorders

To succeed at school, work and in life, you need to be able to identify and explain problems, determine causes, sequence events, make predictions, draw inferences, identify and evaluate options, make and justify your decisions, and solve problems, including challenges involving other people and other variables outside your control. These tasks can be difficult for many people, including many people with Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) or other neurodevelopmental disorders.

The basic framework outlined in this article, with appropriate scaffolding, can be used to support a client’s social and verbal reasoning. When faced with real world challenges, the framework can help support people to think through and communicate their situation, personal goals, choices/options, next steps/actions (with reasons), and predictions about what might be the result or consequences of their actions. It can also be used to look at a difficult situation that has happened (e.g. at school or work) with the benefit of hindsight to talk through what happened, and why.

As speech pathologists focused on providing practical support to people with communication disorders, we want our clients to set and to pursue goals that matter to them, and to participate fully in education, work, social activities of interest, and life. We want our clients to achieve their goals.

But life sometimes isn’t so simple.

Modern approaches to healthcare are based on the idea that outcomes are often determined by complex interactions between a person’s body functions and structures, activities and participation, and environmental and personal factors. Some examples:

- Sometimes, people don’t have as many options as others because of their situations, e.g. socioeconomic status or lack of safety. Sometimes, people don’t know what they want – a very normal situation for many young adults (and adults). At other times, people know exactly what they want, but don’t know what to do (or not do) to get it.

- People sometimes make poor decisions. Some poor decisions result, unexpectedly, in positive outcomes. Conversely, some people make great decisions that, for reasons beyond their control, do not achieve their desired outcome, or can even have negative, unintended consequences.

The framework outlined in this article is a handy tool for some of these ‘real world’ discussions – especially when it comes to planning and interpreting actions that might have significant social, education, work, or life consequences, and when discussing the outcomes and consequences of actions already taken.

It can help clients identify and articulate environmental factors, personal goals, possible actions they will need to take (or avoid) to pursue goals, the results that may come from taking such actions, and the differences between actions within their control, and the results and consequences of such actions (which might not be within their control, in part of in full).

Main source: Urhahne, D. & Wijnia, L. (2023). Theories of Motivation in Education: An Integrative Framework, Education Psychology Review, 35:45

Related articles:

- For reading, school and life success, which words should we teach our kids? How should we do it?

- Oral language: what is it and why does it matter so much for school, work, and life

- Not about ‘fixing’: using the ‘F-Word Framework’ to support children with communication disorders and their families

- Developmental Language Disorder: a free guide for families

- FAQ: “Our family’s paediatrician thinks my child might have a ‘neurodevelopmental disorder’. What does that mean?”