“Why should I let my late-talker play with other kids?” Because play promotes learning: here’s why and how

Yesterday morning, while sunburning myself to a crisp, I watched my sons muck around at Austinmer beach. They were out of earshot, but appeared to be playing a game where Son 1 would “defend” Son 2 from oncoming waves by diving dramatically in front of him, like a bodyguard shielding a President. After protracted negotiations, the boys switched roles. Not for the first time, I pondered how odd kids’ play can be – and how creative, even without props!

Play is weird

When you think about it, the whole idea of play is riddled with contradictions:

- It’s not serious, but it can seem deadly serious – as anyone who’s played Monopoly with my sister knows.

- It’s trivial, but its effects on learning are profound.

- It takes place in a make-believe world, but it helps kids learn to cope in the real world.

- It’s childish, but it’s the foundation for many of humanity’s greatest achievements.

Unlike language, play is not unique to humans: many animals do it too. So why do we play?

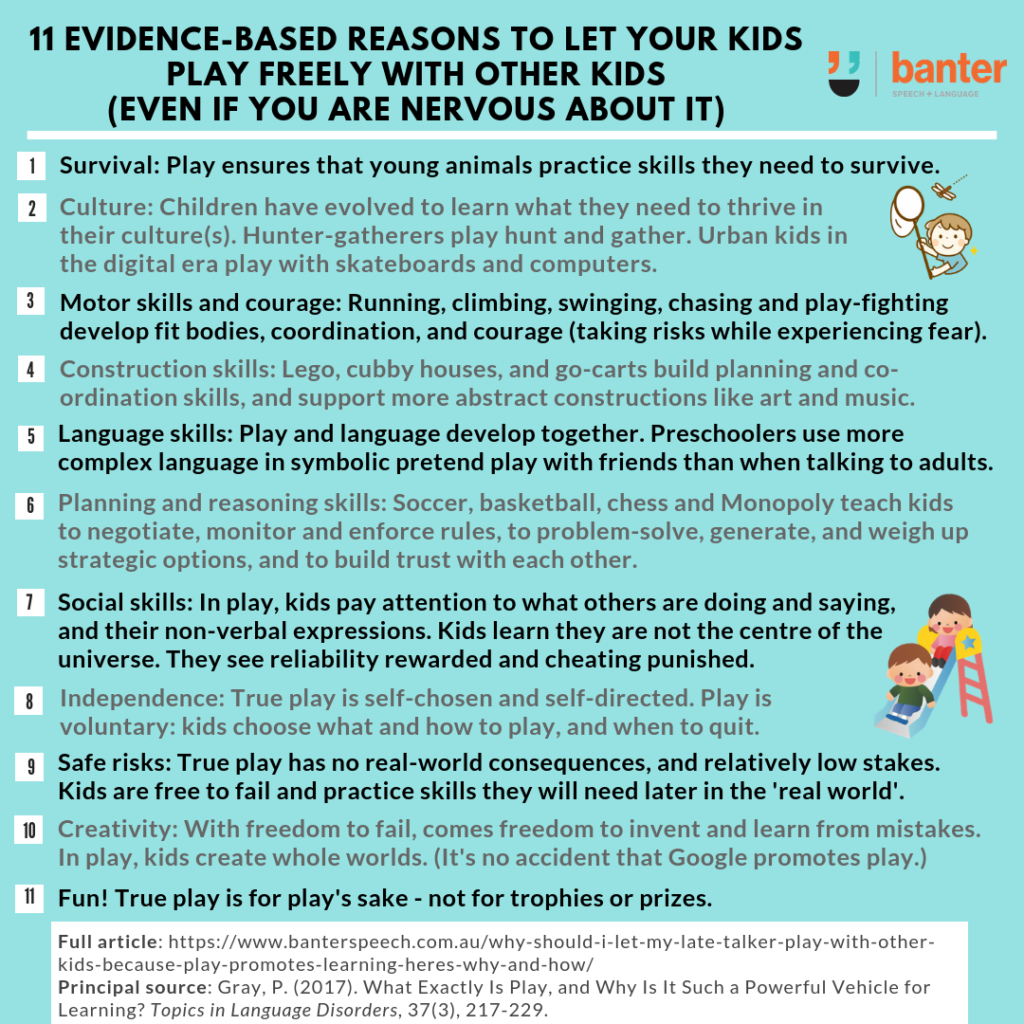

Survival of the playful

After studying animal play, Karl Groos proposed an answer from the Charles Darwin play-book:

“Play came about by natural selection as a means to ensure that animals will practice the skills they need in order to survive and reproduce.”

Groos and his colleagues called this idea the “practice theory of play”. It explains why:

- young animals play more than older animals;

- animal species that have the most to learn, play the most; and

- animals play at skills they need most to survive.

For example:

- lion cubs play at stalking and pouncing; and

- young gazelles play at fleeing and dodging (Gomendio, 1988).

Why do humans play?

Humans have a lot more to learn than lion cubs or gazelles. And we have to learn skills not just to survive, but to fit in with the culture(s) we live in. Groos thinks this is why human kids have a strong drive to watch adults and to incorporate their daily activities into play. For example, anthropologists have found that:

- kids in hunter-gatherer cultures often play at hunting and gathering;

- kids in farming cultures often play at farming; and

- children in many urban cultures today play at computers (e.g. Gray, 2012, Lancy, 2015).

The theory suggests that kids are biologically designed to learn what they need to be successful adults in whatever culture they are born into.

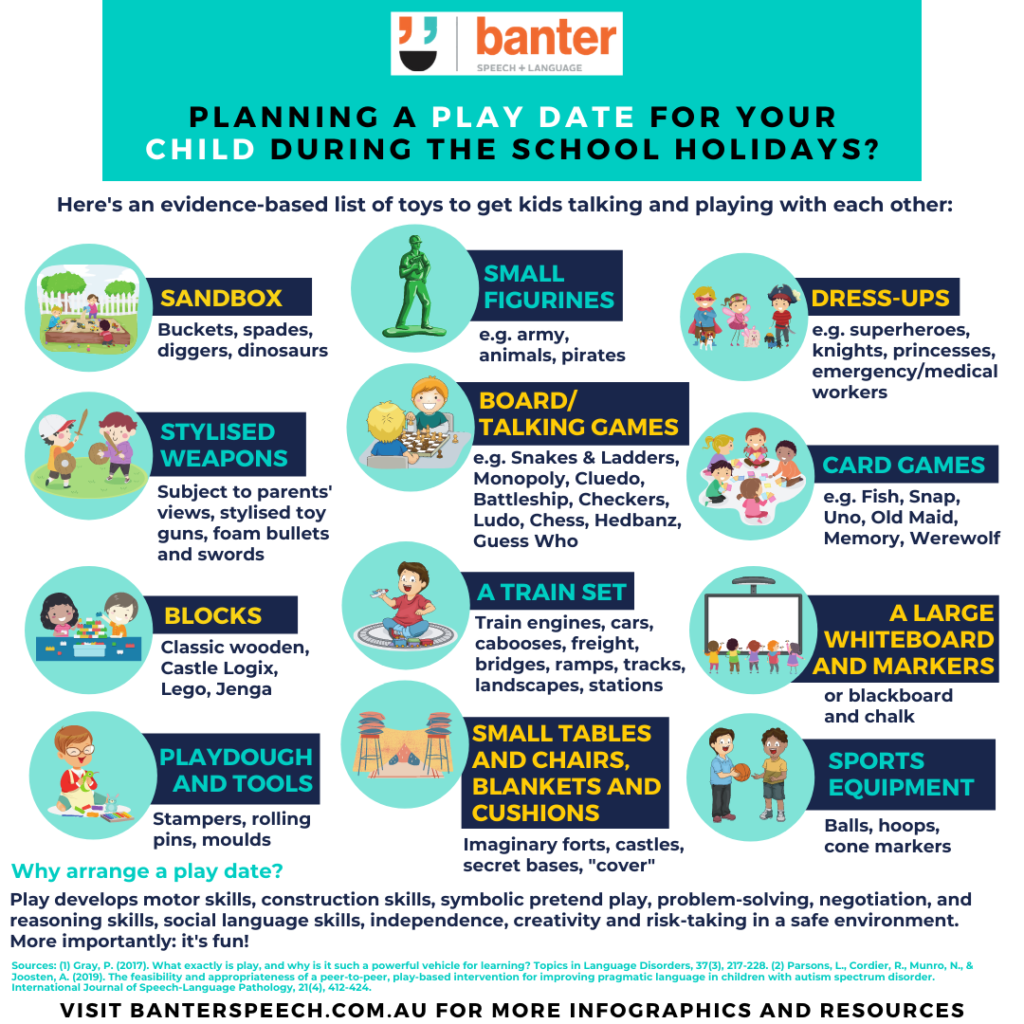

How do kids play – and what does this have to do with language and social skills development

When free to do so, children everywhere play in the following ways:

- Physical/locomotor play, e.g. running, leaping, climbing, swinging, chasing and fighting. All ways to develop fit bodies, coordination, and courage (control of mind and body while taking risks and experiencing fear) (Gray, 2011, Sandseter, 2011). This explains the popularity of party hot-spots like Jungle Buddies and Inflatable World;

- Constructive play, e.g. building tools, cubby houses, and go-carts. Extensions of these skills include art and music play (building sights and sounds);

- Language play, e.g.:

- cooing, babbling and first words (e.g. Bloom & Lahey, 1978). These are playful in that they are produced for their own sake, and not necessarily to get something;

- “crib talk” when kids have monologues and pretend dialogues when alone, e.g. in bed at night (e.g. Kuczaj, 1985);

- word play – funny phrases, puns, rhymes, funny grammatical constructions, idioms, metaphors, similes and allusions, all of which help consolidate kids’ growing understanding of their native language; and

- advanced word play, e.g. poetry;

- Shared fantasy play, e.g. princesses, superheroes, ninja warriors, school teacher and class.

- Pretend play is the foundation of our inventiveness – our ability to think of things that are not actually there – our ability to think of new possibilities, to create hypotheses, to reason deductively, or even think about the weather tomorrow.

- Pretend play feeds language development because it exercises kids’ ability to symbolise. For example, a child might decide that, in a game, a stick is a sword or a horse or a magic wand. This is analogous to a kid learning that a stick is called a stick – an arbitrary label used in the language they are exposed to.

- Developing pretend play skills is often correlated with similar developments in language skills – one reason so much of our early language intervention is play-based. (We’re going to cover this in more detail in a separate article soon.)

- The language used by preschoolers in shared pretend play is far more complex than the language used by kids in structured, adult-led activities or when sitting at a table together eating (Fekonja et al., 2005).

- “Games”: All play has hidden rules. But some games have formal rules and many of them are competitive, e.g. cricket, soccer, chess, and dominoes. When kids play games like these, they are practising their ability to agree to rules and follow them: rules that are essential to all human societies.

- Social play: Kids everywhere are naturally drawn to play with other kids. Historically, social play is far more common that solo play (e.g. Lancy, 2015). Some researchers are concerned that this has changed recently, with many kids nowadays playing mostly alone at home (e.g. Grey, 2017).

So what’s the recipe for effective playing?

So knowing that play boosts learning, how do we help kids play more?

First, we need to identify what true play actually is (and what it isn’t).

(a) Play is self-chosen and self-directed

Play is voluntary. Kids choose to play. They choose what and how to play. They choose when they quit.

If adults step in and direct the action, it’s not true play. As soon as an adult sticks his or her head in, the kids lose their responsibility to come up with their own rules. (When I’m looking to assess or kick-start language in a late-talker, I usually scatter several age-appropriate toys around the room and then watch the kids go. It’s up to them whether they decide to play with anything and, if so, what they choose to play with and how. My key job is to follow their interests and to add language to what they’re doing, without interference.)

In social play – when there are two or more kids in the space – the kids have to make up their own rules and keep it fun (or the others might quit). Often, kids spend more time agreeing the rules than playing the game! This means kids pay attention to what the others are doing and saying, and even their non-verbal expressions. Some researchers think this helps kids to realise that they are not the centre of the universe and that they can fulfil their desires while also helping others meet theirs (e.g. Gray, 2011).

(b) Play is done for its own sake (not for a trophy or reward)

Think about a game to make a sandcastle. Most kids know that the sandcastle is temporary – that the sea will wash it away. But the fun is in making it.

If kids are motivated by a trophy or praise or status, they are not really playing. True play in animals and humans is not a contest to dominate, but instead to be cooperative and done for its own sake. Play is not directed toward a serious real world goal. But here’s the brilliant paradox:

“The enormous educational power of play lies in its triviality.” (Gray, 2017)

Read that statement again. What it means to me is this:

- True play has no real-world consequence.

- True play is safe and fun.

- Nobody is judging, no trophy is on the line.

- True play is not done for food, money, praise or a nice line on a resume.

- No team-mate will be let down in true play.

- Players are free to fail: free to practice a skill for the real world without consequence.

- With freedom to fail, comes freedom to experiment and to learn.

Interestingly, research shows that kids (and adults!) are more creative when they are truly playing around, than when they are trying to impress a judge or win a reward (Amabile, 1996).

Another feature of true play – especially in young kids – is how repetitive it is. Kids do the same thing over and over, perhaps making small changes every time. Repetition and systematic variation are part of practising a skill. Think, for example, of motor skills like learning to climb, or learning to speak.

(c) Play – like language – has rules, but with room for creativity and negotiation

In social play, the rules have to be shared by all the players. But the rules always leave room for negotiation. Different play types have different rules, e.g.:

- in constructive play, everyone must work with the materials agreed to make a specific thing, e.g. a sandcastle;

- in shared fantasy play, players must stick with their roles – they must stay in character; and

- in play fighting, players must mimic real fighting but not hurt each other – no kicking or biting – it’s an exercise in self-restraint.

As a speech pathologist, I’m interested in the similarity here between play and language. Like play, language is based on rules – e.g. phonology, morphology, and syntax – even though we are free to say what we like using those rules. Like play, speaking is a creative, but rule-based activity. In play, as with language, kids practice creating something new that nonetheless follows a set of rules (e.g. Lewis, 2003).

(d) Play is imaginative

In play, kids remove themselves from the “real world” and enter an imaginary world. For example:

- in shared fantasy play, kids create characters and plot;

- in rough and tumble physical play, the fight is pretend – not real;

- in constructive play, kids are building imaginary things, e.g. a castle from sand, or a house from sticks and leaves; and

- in games, players accept an established fictional world, e.g. a world where you need to hit a cricket ball then run quickly to the other end of the pitch to be “safe”.

A human ability – not shared by other animals – is our ability to imagine ways that are not random, but structured by rules, which allows us to produce potentially useful new products. This is perhaps one reason why so many entrepreneurs and innovators – most notably Google – extol their cultures of play and experimenting safely.

In this sense, play is sometimes been described as an “engine for cultural innovations” (e.g. Huizinga, 1955).

Is true play in decline? If so, why does it matter?

In the last 50-60 years, researchers in the USA have documented a steep decline in children’s opportunities and freedom to play without adult interference (e.g. Gray, 2011, 2013; Chudacoff, 2007; Hofferth, 2009; Clements, 2004).

Why?

Here are some candidates:

- A rise in parent fears about the risks of free play away from adults, fueled by often terrifying media reports of abused and abducted children.

- An increase in children’s time spent in school and at homework.

- An increased tendency for kids to be enrolled in adult-led activities out of school, rather than free play.

- A decline in the degree to which neighbours know each other, resulting in a decline in neighbourhood play.

- A decline in family size and the number of kids in many neighbourhoods, resulting in fewer potential playmates (Gray, 2013).

- An increase in non-interactive screen time.

- A decline in age-mixed groups and an increase in kids playing only with kids of the same age. This means young kids don’t get a “play boost” from watching and learning from older kids, and older kids don’t get a chance to practice caring, protecting and leading the younger kids – i.e. to learn by teaching (e.g. Gray, 2011).

Some researchers think there may be a link between the decline of true play, and the decline in mental and social well-being among young people (e.g. Twenge et al., 2010). Some argue that, with reduced freedom to play, children fail to develop a strong sense of control over their own lives (because play is where kids do control their own activities) which, in turn, increases their risk of depression and anxiety (e.g. Gray, 2017).

Other research has revealed some disturbing trends over the last several decades in kids like:

- increased narcissism (e.g. Twenge & Foster, 2010);

- decreased empathy (Konrath et al., 2011); and

- decreased creativity (Kim, 2011).

Leading play researchers, like Professor Peter Gray, suggest that these changes would be predicted if play is in decline because:

- play is a major vehicle for kids to overcome narcissism, attend to others’ needs, and learn to create their own activities; and

- play promotes self-control and creative thinking (e.g. Barker et al., 2014).

Clinical bottom line

In a competitive world, play may seem frivolous and trivial to many parents who of course want the best for their kids. But play promotes learning, often more effectively than structured, adult-led activities.

True play is self-chosen and self-directed by kids, motivated by fun (rather than trophies), ruled-based but creative, and imaginative.

For humans – as with other animals – play has an important evolutionary function. Through no-stakes, imaginary world practice, kids learn vital life skills through self-directed play, including many language and social skills essential for life success.

Arguably, kids have fewer opportunities to play freely with each other than kids 50 years ago. There are some good reasons for this. But deprivation of play may have serious implications for language and social skills development, and mental health – especially for kids at risk or with language and other learning disorders.

As a parent and a speech pathologist in Sydney, I know how hard it is to find opportunities for kids to play freely but safely. But the language, social and other cognitive benefits of free play make it worth the work (and the odd sunburned nose!).

Principal source: Gray, P. (2017). What Exactly Is Play, and Why Is It Such a Powerful Vehicle for Learning? Topics in Language Disorders, 37(3), 217-229. (A highly recommended read.)

Image: http://tinyurl.com/yckdlbyy

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.